Right from Jesus’ first preaching he was in conflict with his fellow townspeople, with the Jewish leaders and was executed by Pilate as a political rebel. Each gospel shows different points of view about Jesus. James Mc Polin SJ explains.

Why Jesus was killed is very clear in the Gospels. He was killed – like so many people before and after him – because of the kind of life he lived, because of what he said and what he did. The fact that it was the Son of God who was killed adds an incomparable depth to the tragedy of his death.

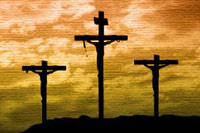

The four Gospels confirm with total clarity the violence of his death. They give maximum space and importance to the suffering and death of Jesus – to an extent that makes them little more than the story of the Passion with a long introduction. But long before these accounts of the Passion in the Gospels, we already have scenes of threat and persecution early in the public life of Jesus.

Early conflicts

Luke describes the first serious attack against him in the scene of the beginning of his mission in support of the poor (Luke 4). The discussion turns on Jesus’ signs in his own region, Nazareth, where he is unwilling to repeat the signs he had done in Capernaum.

Early on we are reminded that ‘no prophet is accepted in his hometown’ (Luke 4:24), but the conclusion of the account is that already his fellow townspeople, full of anger, threw him out of town and wanted to throw him over a cliff.

Threat to the powers

What needs no discussion is the fact that from the very beginning Jesus’ preaching and activity was a radical threat to the religious powers of his time (and indirectly to every oppressive power) and that such a power reacted.

Jesus was essentially a man in conflict and because of this he was persecuted. He got in the way and in the simple words of Archbishop Romero of El Salvador: ‘Those who get in the way get killed.’ Jesus, surrounded by conflict, got in the way.

It is very likely that the Gospel accounts are historically correct when they indicate that enmity and popularity had been part and parcel of Jesus’ life from the start.

Conflict with leaders

Distinct from that incident in Nazareth, which is more local and a bit like a village squabble, Mark also mentions the persecution of Jesus very early in his Gospel.

He describes five controversies between Jesus and the religious leaders. After describing the fifth controversy, when Jesus cured people on the Sabbath, he shows the reaction: ‘The Pharisees went out, and immediately conspired with the Herodians (i.e. followers of Herod) against him, how to destroy him … they watched him, to see whether he would cure him on the Sabbath, so that they might accuse him’ (Mark: Ch 3).

Those responsible

Just before the final entry of Jesus into Jerusalem the evangelists describe how the Scribes and Pharisees put him to the test. No sooner has he reached the temple in Jerusalem than the Scribes and chief priests are looking for him to kill him (Luke: Chs.19, 20).

Once Jesus is in Jerusalem the plots against him are multiplying and the leaders, especially the chief priests, are determined to get rid of him.

John’s Gospel (Chapter 2 to 11) is the one that illustrates – with the greatest wealth of detail – that persecution follows Jesus right through his life.

The Gospels record a constant, increasing persecution such that Jesus’ end was not accidental but the culmination of a necessary process. They name various types of people as responsible for the persecution: Pharisees, Scribes, Sadducees, Herodians and the chief priests. The common people, the masses, whom Jesus chose as his audience, are not listed among those who were responsible for the persecution.

There can be discussion about whether they understood Jesus’ message properly, but they do not persecute him. On the contrary, they provide protection for Jesus because on some occasions ‘fear of the people’ is mentioned as an obstacle to his arrest. In the Gospels there is no suggestion that the people betrayed Jesus or sought his death.

The climax

The conflict intensifies during Jesus’ last week in Jerusalem at the religious trial, which shows the growing hostility of the Jewish leaders, especially the leaders of the priests. They want ‘to put him to death’ and conclude that ‘he deserves death’ (Mark: Ch. 14).

It is important to know why. The jury in the trial, the Sanhedrin or Council (elders of the chief families, high priests, Scribes), hand him over to the Romans. Reasons given in the Gospels are: he wanted to destroy the temple; he criticised certain aspects of this institution and offered people a distinct and opposite alternative which implied that the temple would no longer be the centre of Israel’s political, religious, social and economic life; besides, he was guilty of blasphemy – which was a capital offence – declaring himself to be Messiah and placing himself alongside the God of Israel; they saw him as a false prophet leading Israel astray; he was a dangerous political nuisance whose actions might well call down the wrath of Rome on temple and nation alike.

Pilate and the Romans

Jesus was condemned before the Council on religious grounds, but Pontius Pilate had him executed on the Cross as a political rebel.

We must be more reserved today, especially in the aftermath of the Holocaust, as regards the ‘guilt’ of the Jews. In no way should the whole Jewish people be held responsible for the rejection of Jesus. Even the Jewish authorities of the time do not bear the sole responsibility. Jewish and Roman authorities together, along with Judas, one of Jesus’ own disciples, brought about the downfall of Jesus.

Look at the man

Every year during Holy Week we listen to two long accounts of the Passion of Jesus – on Passion or Palm Sunday we hear the Passion according to Matthew (Year A) or Mark (Year B) or Luke (Year C), while on Good Friday we hear the Passion according to John.

The four accounts are similar and focus on the one Jesus. They show us how Jesus experiences every kind of humiliation – such groundless arrest, desertion by his closest friends, betrayal by a member of his own’ circle, inhuman interrogation and cruel tortures, false accusations and perjuries, the political shifting of blame onto the shoulders of an innocent and defenceless man, condemnation as a law-breaker and a criminal, condemnation to death, physical collapse under the weight of the cross, derision, defamation and the experience of abandonment by God. We are told, to ‘look at the man’ (Jn 19:5). See what people are capable of and what they can suffer.

Mark And Luke

Each evangelist shows a different facet of this suffering man and presents a different picture. Since Matthew differs only slightly from Mark in his portrayal of Jesus during the Passion, we can speak of three different portraits: those of Mark, Luke and John.

Mark shows the abandonment of Jesus which is reversed by God dramatically (the tearing of the temple veil) at the end. From the moment Jesus moves to the Mount of Olives the behaviour of the disciples is portrayed in more negative terms.

While Jesus prays, they fall asleep three times. Judas betrays him and Peter curses, denying any knowledge of him. All flee. Jesus hangs on the cross for six hours, three of which are filled with human mockery.

Jesus’ only word from the cross is: ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’

In Luke’s Gospel the disciples are seen in a more sympathetic light. Pilate acknowledges that Jesus is not guilty; the people are on Jesus’ side. Jesus is always concerned for others, consoling the women who accompany him and healing the slave’s ear.

He forgives those who crucified him. He promises Paradise to the penitent thief. The crucifixion becomes the occasion of divine forgiveness and care. Jesus dies tranquilly, praying: ‘Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.’

John

John’s account presents Jesus as master of the situation. He is in control, aware of what is going to happen and taking the initiative in the events that lead to his death. Under interrogation it is he who puts the questions and dominates the dialogue (John: Chs. 18-19). His last word from the cross is a cry of triumph: ‘My work is finished’ (John: Ch. 19).

These three accounts ‘are given to us by the inspiring Spirit and no one of them exhausts the meaning of Jesus’ (R. Brown).

This article first appeared in The Messenger (March 2002), a publication of the Irish Jesuits.