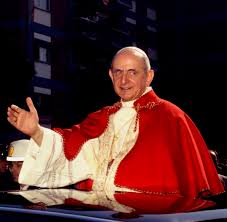

Summary of Pope St Paul VI – Giovanni Baptista Montini. (1897-1978), became a reformigpope in 1963. He reigned during a period of great change and ferment in the Church following the Second Vatican Council.

Giovanni Montini was born September 26, 1897, in Concesio, near Brescia in Italy, the son of a lawyer/journalist/local political figure—and of a mother belonging to the same social background.

Giovanni Montini was born September 26, 1897, in Concesio, near Brescia in Italy, the son of a lawyer/journalist/local political figure—and of a mother belonging to the same social background.

He was in his early years educated mainly at home because of frail health. Later he studied in Brescia. Ordained a priest on May 29, 1920, he was sent by his bishop to Rome for higher studies and was eventually recruited for the Vatican diplomatic service. His first assignment, in May 1923, was to the staff of the apostolic nunciature (papal ambassador’s post) in Warsaw, but persistent ill health brought him back to Rome before the end of that same year. He then pursued special studies at the Ecclesiastical Academy, the training school for future Vatican diplomats, and at the same time resumed work at the Vatican Secretariat of State, where he remained in posts of increasing importance for more than 30 years.

In 1953 he declined an invitation to be elevated to the Sacred College of Cardinals in 1953. In the beginning of November 1954, Pope Pius XII appointed him archbishop of Milan, and Pope John XXIII named him a cardinal in 1958. He was elected pope on June 21, 1963, choosing to be known as Paul VI.

His pontificate was confronted with the problems and uncertainties of a church facing a new role in the contemporary world. His philosophical attitude was often construed by his critics as timidity, indecision, and uncertainty. Nonetheless, many of Paul VI’s decisions in these crucial years called for much courage. In July 1968 he published his encyclical Humanae Vitae (“Of Human Life”), which reaffirmed the stand of several of his predecessors on the long-smouldering controversy over artificial means of birth control, which he opposed. In many sectors this encyclical provoked adverse reactions that may be described as the most violent attacks on the authority of papal teaching in modern times. Similarly, his firm stand on the retention of priestly celibacy (Sacerdotalis caelibatus, June 1967) evoked much harsh criticism. Paul VI later likened the large numbers of priests leaving the ministry to a “crown of thorns.” He also was disturbed by the growing numbers of religious men and women asking for release from vows or who were abandoning out of hand their religious vows.

From the very outset of his years as pope, Paul VI gave clear evidence of the importance he attached to the study and solution of social problems and to their impact on world peace. Social questions had already been prominent in his far-reaching pastoral program in Milan (1954–63).

During those years he had travelled extensively in the Americas and in Africa, centring his attention mainly on concern for workers and for the poor. Such problems dominated his first encyclical letter, Ecclesiam suam (“His Church”), August 6, 1964, and later became the insistent theme of his celebrated Populorum progressio (“Progress of the Peoples”), March 26, 1967. This encyclical was such a pointed plea for social justice that in some conservative circles the pope was accused of Marxism.

Paul’s Concerns for Unity

Paul VI’s human concern found clear expression in his efforts to lessen the long-standing tensions between the church of Rome and other churches and even with those professing no religion at all. He sought closer understanding with numerous religious leaders throughout the world, both Christian and non-Christian, placing more emphasis on those aspects that unite the churches than on those that divide. To show that mutual acquaintance is at the very foundation of any plans or hopes for unity, Pope Paul met with prominent religious leaders from various communities in Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union as well as other countries. Paul VI also set up a special secretariat for nonbelievers, stressing the need of understanding and endeavouring to solve the problems posed by atheism.

Under his guidance the Roman Catholic Church drastically revised its legislation governing marriages between its own members and those who profess other faiths, expressing a firm desire to diminish the threat of human tragedy following possible clashes of individual consciences. For this reason Paul VI’s motu proprio (a type of papal document) was welcomed and praised for its understanding of human problems and its desire to find a satisfactory solution to the problem of mixed marriages without demanding of either side any renunciation of basic principles of conscience.

Paul and Vatican II

The Montini pontificate began in the period following the difficult first session of the Second Vatican Council, in which the new pope had played an important, though not spectacular, part. His lengthy association with university students in the stormy atmosphere of the early days of the fascist regime in Italy, in combination with the generally philosophical bent of his mind—developed by a long-standing habit of extensive and reflective reading—enabled him to bring to the perplexing problems of the times an academic understanding, coupled with the knowledge derived from long years of practical diplomatic experience. Paul VI guided the three remaining sessions of the Second Vatican Council, often developing points he had first espoused as cardinal archbishop of Milan. His chief concern was that the Roman Catholic Church in the 20th century should be a faithful witness to the tradition of the past, except when tradition was obviously anachronistic.

The Montini pontificate began in the period following the difficult first session of the Second Vatican Council, in which the new pope had played an important, though not spectacular, part. His lengthy association with university students in the stormy atmosphere of the early days of the fascist regime in Italy, in combination with the generally philosophical bent of his mind—developed by a long-standing habit of extensive and reflective reading—enabled him to bring to the perplexing problems of the times an academic understanding, coupled with the knowledge derived from long years of practical diplomatic experience. Paul VI guided the three remaining sessions of the Second Vatican Council, often developing points he had first espoused as cardinal archbishop of Milan. His chief concern was that the Roman Catholic Church in the 20th century should be a faithful witness to the tradition of the past, except when tradition was obviously anachronistic.

Upon the completion of the council (December 8, 1965), Paul VI was confronted with the formidable task of implementing its decisions, which affected practically every facet of church life. He approached this task with a sense of the difficulty involved in making changes in centuries-old structures and practices—changes rendered necessary by many rapid transformations in the social, psychological, and political milieu of the 20th century. Paul VI’s approach was consistently one of careful assessment of each concrete situation, with a sharp awareness of the many varied complications that he believed could not be ignored and most famous for reaffirming the Catholic church’s ban on artificial contraception.

A wide swath of Catholics, especially in the U.S. and Europe, were furious over Paul’s decision. They were convinced that the ban would be lifted and that Paul was shutting down the reforms that had begun a few years earlier with momentous changes adopted by the Second Vatican Council. Many conservatives, on the other hand, hailed “Humanae Vitae” for reasserting traditional doctrine. This division foreshadowed the deep splits that have lasted over decades.

Paul VI, the Refomer

Chief among his achievments was his call for a more missionary church that would be open to the world and one that would dialogue with other Christians and other believers, and with nonbelievers, too. “For us, Paul VI was the great light,” Pope Francis recently said of Paul VI referring to his years as a young priest. He was also a vocal champion of the church’s social justice teachings, and he sought to embed those concepts as foundation stones of Catholic doctrine. He also implemented a system of regular meetings of bishops, called synods, to promote a more collaborative, horizontal church.

Paul VI, an ‘Evangelical’ Pope.

Pope Francis said that the key to Paul’s pontificate was his 1975 exhortation on evangelization, Evangelii Nuntiandi (“On Proclaiming the Gospel”), which Francis has called “the greatest pastoral document written to date.” In that landmark document — largely overshadowed by the contraception encyclical, Paul VI said that the church itself “has a constant need of being evangelized,” and he wrote that people today listen “more willingly to witnesses than to teachers,” so Catholic leaders above all must practice what they preach. “The world calls for, and expects from us, simplicity of life, the spirit of prayer, charity towards all, especially towards the lowly and the poor, obedience and humility, detachment and self-sacrifice. Without this mark of holiness, our word will have difficulty in touching the heart of modern man. It risks being vain and sterile,” Paul wrote in words that could have come from the pen of Pope Francis. In fact, in November 2013, Francis sent a personal representative to a meeting of the U.S. bishops and had him read those passages to the hierarchy, followed by clear instructions that Francis, like Paul before him, “wants ‘pastoral’ bishops, not bishops who profess or follow a particular ideology.” He discarded the papal triple tiara and other trappings of the monarchical papacy, sending a message “that the pope was not a king, but a bishop, a pastor, a servant,” as the website of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops put it in one of its tributes.

Paul VI, a Pilgrim pope

Elected in 1963 on the death of St. John XXIII, amid intense debates among bishops at the Second Vatican Council, the former Cardinal Giovanni Montini inherited the difficult task of seeing the council through to its conclusion in 1965. In the following years, he pushed through the council’s changes, including updating the liturgy from Latin to the vernacular and completing a major reorganization of the Roman Curia. Paul was the original “pilgrim pope,” the first pontiff to travel outside Italy in the modern era. On his first trip, Paul met the Eastern Orthodox patriarch in Jerusalem in 1964, and during Paul’s eight other foreign journeys he visited Asia –where a knife-wielding artist in the Philippines tried to stab him — Africa and Latin America. In 1965, Paul became the first pope to visit the U.S., and delivered a ringing denunciation of war to the United Nations General Assembly. Paul’s motto: “No one defeated; everyone convinced.”

Pope Paul was never destined to become a star the way some other popes were. “Critiqued by the left over birth control and by the right for reforms to the liturgy, Paul in his last years was depicted as a Hamlet-like figure of equivocation.

His end did seem tragic, as he aged rapidly under the burdens of the office, governing the church at a time of massive social upheavals abroad and close to home. In the spring of 1978, a long time friend of Paul’s and a prominent Italian political leader, Aldo Moro, was kidnapped and executed by left-wing terrorists in Italy despite an impassioned appeal by the anguished pope. Pope Paul died of a heart attack three months later, “one of the holiest and most loving of Popes” but also “one of the saddest,” commented the editors of the Catholic magazine Commonweal at the time.

His end did seem tragic, as he aged rapidly under the burdens of the office, governing the church at a time of massive social upheavals abroad and close to home. In the spring of 1978, a long time friend of Paul’s and a prominent Italian political leader, Aldo Moro, was kidnapped and executed by left-wing terrorists in Italy despite an impassioned appeal by the anguished pope. Pope Paul died of a heart attack three months later, “one of the holiest and most loving of Popes” but also “one of the saddest,” commented the editors of the Catholic magazine Commonweal at the time.