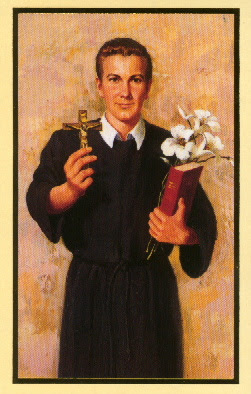

Summary: St Gerard Majella, a young 18th century Italian who ‘eloped’, so to speak, in order to join the Redemptorists. St Gerard Majella, one of Ireland’s best-loved saints, known here particularly as the ‘mothers’ saint. He was canonized over 100 years ago .

Robert McNamara CSsR tells us the St Gerard Majella story

Obvious frailty

Gerard was born on Saturday, April 6, 1726, in the picturesque southern Italian town of Muro. His parents Domenico and Benedetta had him christened on the day of his birth, because of his obvious frailty. They had already lost a baby boy, also called Gerard, who only lived a week. Twelve years later, Benedetta would be left a widow, with four young children to support. Gerard’s education was cut short; he was apprenticed to a local tailor, and later became valet to the temperamental bishop of Lacedonia.

Gerard was born on Saturday, April 6, 1726, in the picturesque southern Italian town of Muro. His parents Domenico and Benedetta had him christened on the day of his birth, because of his obvious frailty. They had already lost a baby boy, also called Gerard, who only lived a week. Twelve years later, Benedetta would be left a widow, with four young children to support. Gerard’s education was cut short; he was apprenticed to a local tailor, and later became valet to the temperamental bishop of Lacedonia.

Gerard’s piety was evident from early on. He seems to have been blessed with a real hunger to know the Lord better, and spent many hours in prayer. At the same time, as recent research shows, he was anything but the tortured aesthetic portrayed by pictures circulated after his death. We have it on good authority that he was immensely charming, had a great sense of fun, and loved to play practical jokes.

Gerard’s piety was evident from early on. He seems to have been blessed with a real hunger to know the Lord better, and spent many hours in prayer. At the same time, as recent research shows, he was anything but the tortured aesthetic portrayed by pictures circulated after his death. We have it on good authority that he was immensely charming, had a great sense of fun, and loved to play practical jokes.

Stuff of romance

The circumstances of Gerard’s entry into religious life are legendary in Redemptorist circles, and are the stuff of romance. In 1749, the Redemptorists came to Muro to give a mission. Gerard was then 23 years old. He met with the superior of the mission, Fr Cafaro, and begged to be admitted to the Redemptorist Congregation. Though impressed by Gerard’s obvious sincerity and holiness, Gerard’s bad health – he looked “more a ghost than a man,” said a witness – and lack of formal education put Fr Cafaro off. He refused to accept Gerard, and told him to forget about the idea.

Meanwhile, Benedetta had found out about the plan. On the day the missioners were leaving town, she locked Gerard in his bedroom so he could not follow them. But Gerard made a rope from the sheets, lowered himself down, and pursued the missioners out of town. A note left behind declared that he had gone off to become a saint.

Twelve miles later he caught up with the mission team. On a country road that May afternoon, Gerard knelt before Fr Cafaro and again begged to be allowed to join the Redemptorists. Eventually, Fr Cafaro gave in, sending Gerard to the Iliceto community with some of the most famous words in the Redemptorist annals: “I am sending you a useless brother.”

Love of God and neighbour

Love of God and neighbour

Gerard’s witness as a Redemptorist could be summed up in his living out what Jesus termed the two hinges of good religion: love of God and love of neighbour. For Gerard, these were simply two sides of the same coin.

He had an amazing capacity for pure, simple, agenda-free friendship. If there was any agenda, it was simply to share the liberating message of Jesus Christ, who can make all things new. Gerard had an almost psychic ability to sense the suffering of another and try to alleviate it, to let passion become compassion.

Fr John Carr recalls an incident when Gerard, on the way to the city of Sant’ Agata di Puglia, found himself at a crossroads. There he met a man who looked deeply troubled, with “a face with the melancholy and despair of sin.” (2) Just to make conversation, Gerard asked him where he was headed, and was abruptly told to mind his own business. Gerard kept chatting, the man continued to ignore him, and tried to pass him out. Gerard reached out, gently held the man by the shoulders, looked him in the eye, and said: “I know what you’re going through. God has sent me here for you. Don’t doubt it.”

This hit home, and the man broke down. They sat there by the road, and years of pain came pouring out in the presence of Gerard’s healing heart. Surely, we cannot miss the overtones here of the Jesus of the Emmaus road who meets each of us at our particular crossroads, asking us, “What things are going on in your life?”

Even considering the exuberance of the southern Italian temperament, Gerard’s literal invasion of the man’s space would be most politically incorrect for us today. We value privacy at all costs. However, in the wake of the Celtic Tiger, this privacy has come at a high price. It is often a privacy without compassion, the privacy, not of the citizen but of the consumer. I walk on by because the other is of no value to me personally. It’s what he can do for me that matters.

Bedrock of Christianity

Gerard’s witness calls us back to that bedrock of Christianity and, indeed, humanity: community. He challenges us to join him in stumbling on to that mysterious paradox at the heart of Christianity: that it is in losing myself that I will find all, that I should care, that it is through showing compassion for others that I will live an even more rich and varied life. That said, Gerard asks us, how will people know we care if we don’t risk reaching out to them? There are worse fates then being told to mind your own business. Christians are their brothers’ and sisters’ keepers.

Gerard’s devotion to the passion of Christ enabled him to see the suffering Christ reflected in broken humanity. His love of neighbour was thus the flip side of his love of God. He was obviously a person of prayer from early on. This means that he was someone blessed with the courage to take time to tap into the centre, to listen to deeper rhythms and truer motivations. As he himself often said, “We cannot talk about God unless we first talk to God.”

Christ can house Himself in our heart and we can become one as he did with St Gerard.

Deep longing

If, as Richard Rohr says, spirituality is what you do with your “deep longing”, Gerard’s witness speaks to a world which seems increasingly resistant to depth. This is a resistance which takes many forms. In an increasingly technocratic society, for example, the skill of reflective thinking is not encouraged, because it is not “practical”. What you see is what you deal with. The tawdry, the vulgar, and the shallow rule the day. Idealism is equated with foolishness. Even our conversation is affected, with a great paucity of vocabulary becoming more evident.

We are afflicted with a surfeit of shallowness, and are often running on empty from surface-level living. We’re tempted to get tired of life early, for “what more is there?” we ask. We have it all, know it all, have done it all. In Patrick Kavanagh’s apt phrase: “through a chink too wide there comes in no wonder.”

Gerard’s warm relationship with the Lord dares us to wonder again, speaks volumes to contemporary people simultaneously longing to be centred and yet fleeing from such an encounter. While we know that living on the surface will not sustain us, we can be afraid of what we’ll find when we go deeper.

Homing device for God

Gerard’s experience reassures us of the truth of something Karl Rahner would say centuries later, that every human being comes complete with a sort of inbuilt homing device for God, and that we need not be afraid to respond, because in the silence we will receive not condemnation, but hospitality, a welcome home to the heart of the Father.

As Pope John Paul II put it so beautifully in Tertio Millennia Adveniente: “The whole of the Christian life is like a great pilgrimage to the house of the Father, whose unconditional love we discover anew each day.” Gerard was not afraid to visit and revisit the place of the centre, and, in the best Christian tradition, those visits spilled over into social responsibility, the flip of the coin again.

Invited to the splendid feast

On Sunday, August 31, 1755, Gerard returned to the Caposele monastery so exhausted, according to Fr Tannoia, that he looked more like a dead than a living man. Never healthy at the best of times, his final journey had begun. He took to his bed, suffering from sustained bouts of haemorrhaging and dysentery. The pain was terrible. A letter he dictated at the time contains the following lines: “I am writing this from my cross … the pain is so very, very severe … I was to die by the lance, but the lance seems to have been mislaid, so I must go on suffering…” Despite such sentiments, there were times, witnesses recall, that Gerard looked like one invited to some splendid feast. This generous sharer of Christ’s redeeming love passed to eternal life on the night of October 16, 1755, aged 29.

In a letter to a nun, Gerard once wrote the following wise lines: “There is no need to dwell on the surface of daily events, but rather, to scrutinise them with the eyes of faith. The project and the loving presence of God are real, even beneath the crust of events that at first glance seem to be harsh.” When we can see that, “it is possible to live always in serenity, knowing well that in God’s plan lies our happiness and fulfilment.”

The beat of ‘the living goodness

In the last few months, we lost one of the great prophets of the church, Columban Fr Niall O’ Brien. Fr Niall and the ‘Negros Nine’ gained international headlines in the mid-80s when they were falsely imprisoned on a trumped-up murder charge in the Philippines. It was a covert way of silencing Fr Niall’s voice, a voice constantly raised on behalf of the oppressed sugar workers.

Fr Niall’s books, Revolution from the Heart, and Seeds of Injustice make for fascinating reading. They tell the story of a young, raw Irish missionary who left these shores in the 1960’s to go and “convert” the Filipinos. After awhile, Fr Niall stumbled on the joyful and liberating discovery that the Holy Spirit was there already, and all he had to do as a priest was to “discover, share, and affirm” the Spirit’s gifts.

While he had always tried to live in a way that shared the experience of the Filipino people, imprisonment opened up a whole new dimension to that. Fr Niall recalled the kindness and sympathy of many prison guards, who were as much victims of the system as their Charges. In one memorable passage, he recounts how he and his colleagues were advised to install chicken wire to prevent grenades from being lobbed in. And yet, in the midst of all this uncertainty, Fr Niall was still able to declare that “deep in the heart of the universe there beats a living goodness.”

What defines a saint

It is precisely this double-edged ability to engage with the messiness of human existence and to see deeper dimensions to it – in religious terms, God shining through it – that defines any saint or inspirational figure. This is because the lessons gleaned from such engagement are timeless, and speak to us as much today as when they happened.

Two such experiences from St Gerard’s life are cases in point: Gerard as victim of false accusation, and Gerard as peacemaker.

In Gerard’s day, if a young woman wished to enter the convent, she needed a substantial dowry. This presented a problem in the cases of young women from poorer families. In such cases, Gerard would often discreetly raise the money from wealthy contacts.

Such was the case in the spring of 1754, with a young woman called Neria Caggiano. It was a name Gerard would never forget. Gerard raised the money for her, Neria entered the convent, got homesick, and left three weeks later. She was embarrassed and angry at having to leave, and, unfortunately, this was taken out on Gerard.

She began to gossip about him in a way which implied that he was not the saint people thought he was, particularly with regard to his relationship with a certain Nicoletta. Neria fabricated a story about Gerard and Nicoletta, told it to a priest, who promptly reported it to Alphonsus de Liguori, the Rector Major of the Redemptorists.

Alphonsus summoned Gerard, read him the accusation, and asked him if he had anything to say. Like the Lord before Pilate, Gerard remained silent. Alphonsus ordered him to stay in the monastery, with no contact with the outside world, and, worst of all, Gerard was forbidden to receive the Lord in Holy Communion. However, as he said at the time, “it is enough to have Jesus in my heart.” They could not take that away from him.

Three months later, Neria was seriously ill. She wrote a letter retracting everything, and Gerard’s name was cleared. A distraught Alphonsus summoned Gerard again, and asked him why he had not spoken in his own defence. Gerard simply replied that to do so was forbidden by the Rule of Redemptorist religious life, and that he knew that the Lord would work things out.

Three months later, Neria was seriously ill. She wrote a letter retracting everything, and Gerard’s name was cleared. A distraught Alphonsus summoned Gerard again, and asked him why he had not spoken in his own defence. Gerard simply replied that to do so was forbidden by the Rule of Redemptorist religious life, and that he knew that the Lord would work things out.

In a world where the rights of the individual are primary, and where we loudly and vocally assert our autonomy at every turn, such blind trust seems laughable, until we remember that the constant, desperate assertion of our individuality masks the number one heresy around today: that I am in sole control of my own destiny. Gerard’s blind trust calls us back to a radical dependence on God’s providence, a massive act of faith of which most of us today would be incapable.

Also, Gerard’s experience shows us that part of the pursuit of justice in Ireland today lies in not assuming that all priests and religious accused in abuse cases are guilty as charged. Some of them may be the casualties of the bush fires of gossip.

Gerard, the peacemaker

In 1753, the year before Gerard met Neria, the Carusi family was split down the middle by a blood feud which made The Godfather look like child’s play. Twenty-year-old Francesco had had a row with his cousin Martino, challenged him to a duel, and been killed in the process. Francesco’s parents had never forgiven or forgotten. In the words of an early Redemptorist commentator, they had “entrenched themselves within that most formidable of fortresses, a hating heart.”

Gerard was called to the scene. Signore Carusi welcomed him politely, but made it clear that he was not interested in a reconciliation. Gerard tried again a few days later, and this time he seemed to be making progress until Teresa, Francesco’s mother, burst into the room holding a bundle of cloth: the bloodstained clothes in which her son had been murdered. Flinging them down before her husband, she screamed: “Look at these clothes and then go and be reconciled! The blood of our Francesco cries out for vengeance!” Signore Carusi began to backtrack.

But if the Carusis had a blood stained relic, Gerard had one as well. Placing his Redemptorist mission cross on the floor, he asked them to walk on it. They refused to do so. Then he said to them: “Don’t you see the inconsistency in your position? You refuse to tread on the crucifix, yet by your refusal to forgive, you are continuing the crucifixion of Christ and his people!” They got the message and were reconciled with Martino’s family.

Gerard’s witness here is a gospel one: that the way of peace and reconciliation is the way of Christ the Redeemer, that peace can break out in even the most unpromising situations, and that the cross shines through all human suffering, giving it meaning, and linking us all. Christ’s passion is compassion.

A lesson we may be learning

In the midst of the U.S. war on Iraq, in the wake of those shocking photographs of torture perpetrated by both Americans and Iraqis, we could be tempted to despair, and ask ourselves, do we ever learn? I dare to believe that we are learning.

I spent most of the past year and a half studying in the United States, and was there when the war against Iraq broke out. What was most striking to me, and what seems not to have been well reported here, was the sheer volume of American resistance to that war. On February 14 last year, for example, three million people descended on Washington to protest against the war. Considering that this began as a regional conflict and not as a global war, such a level of resistance was remarkable.

When I look at it through Christian eyes, I can only put it down to the hope that the awareness of the common destiny of humanity is finally dawning upon us, that truth that organisations like Greenpeace and Ploughshares have been telling us all along: that we’re all in this together, that along with the animals and plants we share this sacred earth, that what divides us is far outweighed by what we have in common.

Scripture advises us to praise illustrious men, a sentiment from which Gerard would have instinctually shied away. Nevertheless, it is only right that we celebrate the centenary of the canonisation of this young man who was wise beyond his 29 years. His humble but courageous witness teaches us timeless lessons in the Christian life. By following his example, we can be guaranteed to see Jesus more clearly, love him more dearly, and follow him more nearly, day by day.

1. O’Toole, Fintan. After the Ball. Dublin: New Island, 2003, p. 3.

2. Carr, John, C.Ss.R. St Gerard Majella. Dublin: Clonmore, 1959, 170.

3 From a letter to Sr Maria deJesus, April 25, 1752, quoted in: Londono, Noel (ed). Saint Gerard Majella- his Writings and Spirituality. Liguori: Missouri, 2002, p. 110.

This is a combination of two articles that appeared in Reality (June and July/August, 2004), a publication of the Irish Redemptorists.