By Cian Molloy - 14 May, 2018

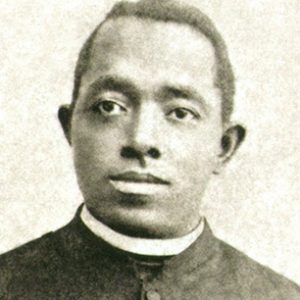

The Catholic Church is one step closer to officially recognising its first Afro-American saint, with major progress achieved by the cause for the canonisation of Fr Augustus Tolton, the United States’ first black diocesan priest.

The Catholic Church is one step closer to officially recognising its first Afro-American saint, with major progress achieved by the cause for the canonisation of Fr Augustus Tolton, the United States’ first black diocesan priest.

Typically, there are two major steps on the way to being officially recognised as a saint. Firstly, the candidate must be declared “venerable” and then, following proof of a miracle obtained by their intercession, they are beatified and declared “blessed”, with a second miracle then required before they can be declared a saint.

As part of the process of being declared venerable, the candidate’s life and deeds are scrupulously examined and a report, known as a positio, is prepared and presented to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints in the Vatican.

Fr Tolton’s positio was approved recently by the Vatican’s historical consultant, said Bishop Joseph Perry, auxiliary in Chicago and the postulator for the Afro-American’s cause, which was opened by the late Cardinal Francis George, Archbishop of Chicago, in 2011.

“They have a story on a life that they deem is credible, properly documented,” said Bishop Perry. “It bodes well for the remaining steps of scrutiny — those remaining steps being the theological commission that will make a final determination on his virtues.

“Then it goes to the cardinals and archbishops who are assigned to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints. Once they approve it then the prefect of that congregation takes the case to the Pope.”

Born into slavery in Missouri in 1854, the young Augustus Tolton was baptised and reared a Catholic by his parents, both of whom were Catholic at the stipulation of their “owners”, who ran two adjoining farms.

At the time of the American Civil War, Augustus’s father – Peter Paul Tolton – escaped to join the Union Army and, shortly afterwards, his mother – Martha Jane Tolton (née Chisley) – also fled north, taking her four children with her. Chased by bounty hunters, the family had to make a perilous crossing over the wide Mississippi River before they would be free.

They made their way to Quincy, Illinois, where Martha, Augustus and his older brother Charley found work in a tobacco company making cigars. There an Irish Augustine priest, Fr Peter McGirr, from Fintona, Co. Tyrone, gave Augustus the opportunity to attend the parish school during the winter months when the factory was closed. Some parishioners objected to having a black student at their children’s school, but Fr McGirr held firm.

Augustus later continued his studies with other Augustinian priests and, partly as a result of this, he too felt a call to priesthood. However, no American seminary would take him as a student, so Fr McGirr organised for him to attend the Pontifical Urbaniana University in Rome, where the young American became fluent in Italian, while also studying Latin and Greek.

Augustus Tolston was ordained in Rome in 1886 at the age of 31. He expected to be sent on the missions in Africa, but instead was directed to return to America to serve the black community there. The American Civil War had ended the previous year and emancipated slaves were fleeing the south to find a better life in the industrial north of the United States.

Fr Tolton celebrated his first public Mass at St Boniface Church in Quincy and attempted to organise a parish in the town, but he was met with hostility by some white Catholics, who were mainly of German origin, and some black Protestants, who were anti-Catholic.

Such were the racial tensions at the time that when he started to organise a new church and school in Quincy, his dean, who was also black, tried to convince him to turn white worshippers away from his celebrations of the Mass. This was something that Fr Tolton refused to do.

Indeed, he was such a good preacher that many white people filled the pews for his Masses, along with black people. This upset some of the white priests in Quincy, who made life very difficult for him as a result. After three years, Tolton moved north to Chicago, at the request of Archbishop Patrick Feehan, to minster to the black Catholic community here.

Tolton worked tirelessly for his congregation in Chicago, to the point of exhaustion, and on July 9, 1897, he died of heat stroke while returning from a priests’ retreat. He was 43.

While working on the positio, the Vatican’s historical consultants asked Bishop Perry why it took the Archdiocese of Chicago so long to open the cause for the canonisation of someone who had died over a hundred years ago.

In an interview with the archdiocese’s newspaper, the Chicago Catholic, Bishop Perry said: “We told them that African Americans basically had no status in the church to be considered at that time. Some people didn’t think we had souls. They were hardly poised to recommend someone to be a saint. And then in those days there were hardly any saints from the United States proposed.”

Details of two miracles believed to have been obtained through Tolton’s intercession have been sent to Rome. Bishop Perry said: “We’re hoping and our fingers are crossed and we’re praying that at least one of them might be acceptable for his beatification.”

Tolton did not speak out publicly against the racist abuse he encountered from his fellow Catholics. Rather, throughout his ministry, he preached that the Catholic Church was the only true liberator of blacks in America.