|

|

![]() “Misericordia in Latin, Trócaire in Irish or Mercy in English: this has become a keyword in the ministry of Pope Francis,” the President of the Vatican’s high profile Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, Cardinal Peter Turkson, stated on his recent visit to Ireland.

“Misericordia in Latin, Trócaire in Irish or Mercy in English: this has become a keyword in the ministry of Pope Francis,” the President of the Vatican’s high profile Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, Cardinal Peter Turkson, stated on his recent visit to Ireland.

Delivering the Trócaire 2015 Lenten Lecture in St Patrick’s College Maynooth, he explained that as in the Scriptures, Pope Francis often associates mercy and tenderness, appealing to the faithful in Evangelii Gaudium to bring about a “revolution of tenderness”.

For “there is no longer room for others, no place for the poor” when our interior life becomes caught up in its own interests, or when our national life and economy become caught up in their own interests,” Cardinal Turkson quoted the Pope.

The 66-year-old, who was the first Ghanaian ever to be made a cardinal, paid tribute to Irish people’s “outstanding reputation for generous giving and for commitment to development issues”.

He noted that, according to the Charities Aid Foundation World Giving Index, Ireland is consistently among the five most generous countries of the world and is the most generous country in Northern Europe.

He said he was paying tribute to this tremendous generosity and compassion on behalf of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace and to the “outstanding work” of Trócaire.

“When I come to Ireland, I already know that people in Ireland really do care about outreach to those in need, commitment to development aid, and engagement with the issues of international development,” he stated.

As the development agency of the Irish Bishops’ Conference and a member of Caritas Internationalis, Trócaire, the Cardinal said, “is a worthy ambassador of Ireland’s compassion and concern for justice across the world. Its professionalism and experience also make it a world leader and a respected voice in terms of insight into issues of international development and a leader in working for a more just world.”

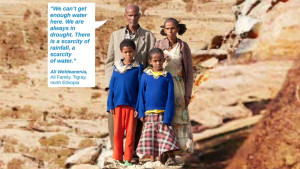

Mahlet is thirteen years old and lives in Sebeya in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia. Last year, it only rained three times in this area. As a result, crops failed, people became hungry and animals were forced to eat dried twigs and cactus plants. This happened because of climate change. This area used to be green and swampy but now is a barren dessert, a wasteland where nothing grows.

In his Trócaire address, titled ‘Integral ecology and the horizon of hope: concern for the poor and for creation in the ministry of Pope Francis’, the Ghanaian prelate highlighted that, “The Holy Father has echoed the sense of crisis that many in the scientific and development communities convey about the precarious state of our planet and of the poor.”

Just ahead of his arrival in Ireland, the President of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace launched a new Church initiative aimed at protecting the Amazon basin and its inhabitants.

The Pan-Amazonian Ecclesial Network aims to promote the economic development of the region while managing Amazonian natural resources in a way that respects human dignity.

This network is the result of cooperation between the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, the Latin American Bishops Conference, local dioceses in the region as well as religious orders, and other Catholic groups working in the sphere of the Amazon River.

This network is the result of cooperation between the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, the Latin American Bishops Conference, local dioceses in the region as well as religious orders, and other Catholic groups working in the sphere of the Amazon River.

Nine countries are directly affected: Brazil, Guyana, Surinam, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Paraguay and Bolivia.

He warned that the “threats that arise from global inequality and the destruction of the environment are inter-related and are the greatest threats we face as a human family today”.

“We all have a part to play in protecting and sustaining what Pope Francis has repeatedly called ‘our common home’,” he observed.

Addressing members of the Irish hierarchy, including the vice president of the Irish Bishops’ Conference, Archbishop Diarmuid Martin, Bishop William Crean, President of Trócaire, and Bishop Denis Nulty of Kildare & Leighlin, Cardinal Turkson outlined Pope Francis’s four principles of integral ecology which he sees as the basis for an authentic and sustainable approach to human ecology and development and the care of the natural environment.

| [vimeo 116763772 w=500 h=281] |

“At the heart of this integral ecology” is the call to “a changing of human hearts in which the good of the human person, and not the pursuit of profit, is the key value that directs our search for the global, the universal common good”.

The Vatican-based prelate said that for the Pope, integral ecology, as the basis for justice and development in the world requires “a new global solidarity”.

He told the bishops, priests, seminarians, Religious and laity who attended his address that Pope Francis’ encyclical letter on human ecology will explore the relationship between care for creation, integral human development and concern for the poor and will be published “before the summer” and in time for the Pope’s visit to New York and address to the UN in September.

Rev Professor Michael Mullany, Vice President of St Patrick’s College Maynooth, Cardinal Peter Turkson, Dr Lorna Gold, Head of Policy & Advoacy at Trócaire and Eamon Meehan, Executive Director of Trócaire.

The Cardinal, who is widely considered ‘papabile’, urged his audience to “give great attention to the forthcoming encyclical” as “we confront the threat of environmental catastrophe on a global scale.”

Describing 2015 as “a critical year for humanity” Cardinal Turkson said the coming 10 months are “crucial” for the decisions about international development, human flourishing and care for the common home we call planet Earth”.

He explained that this was because in July the Third International Conference on Financing will take place in Addis Ababa; in September the UN General Assembly will agree a new set of sustainable development goals for the period up to 2030; and in December, the Climate Change Conference in Paris will make plans and commitment to slow or reduce the pace of global warming.

In responding to “the precarious state of our planet and of the poor”, our efforts require an integral approach to ecology, not one limited to scientific, economic or technical solutions.

Drawing from Catholic Social thought, rooted in the Sacred Scriptures and natural reason, the Pope’s first principle of integral ecology, he explained, is the call to protect and care for both creation and the human person which are reciprocal concepts and together make for authentic and sustainable human development.

The Cardinal warned that the “threats that arise from global inequality and the destruction of the environment are inter-related and are the greatest threats we face as a human family today”.

He identified the four principles of integral ecology reflected in the ministry and teaching of Pope Francis as:

(1) the call (to all people) to be protectors is integral and all-embracing;

(2) care for creation is a virtue in its own right (relationship between nature and man);

(3) necessity to care for what we cherish and revere (religious voice and sustainable development and environmental care);

(4) the call to dialogue and a new global solidarity (everyone has a part to play, not matter how small, and this can make a difference) based on the fundamental pillars that govern a nation, its nonmaterial goods: life, family, integral education, health including the spiritual dimension of well-being, and security.

![]() I First Principle: The call to be protectors is integral and all-embracing

I First Principle: The call to be protectors is integral and all-embracing

The first principle of Pope Francis’ integral ecology underlines that the call to be protectors is integral and all-embracing. “We are called to protect and care for both creation and the human person. These concepts are reciprocal and, together, they make for authentic and sustainable human development.”

According to Cardinal Turkson, this is clearly not “some narrow agenda for the greening the Church or the world. It is a vision of care and protection that embraces the human person and the human environment in all possible dimensions.”

Referring to Pop e Francis’ morning homily at Santa Marta on 9 February, the Cardinal highlighted that the Pontiff had stated that “it is wrong and a distraction to contrast ‘green’ and ‘Christian’. In fact, “a Christian who doesn’t safeguard creation, who doesn’t make it flourish, is a Christian who isn’t concerned with God’s work, that work born of God’s love for us.”

e Francis’ morning homily at Santa Marta on 9 February, the Cardinal highlighted that the Pontiff had stated that “it is wrong and a distraction to contrast ‘green’ and ‘Christian’. In fact, “a Christian who doesn’t safeguard creation, who doesn’t make it flourish, is a Christian who isn’t concerned with God’s work, that work born of God’s love for us.”

Cardinal Turkson also identified how the writings of Francis’s predecessors John Paul II and Benedict XVI on human ecology had foreshadowed his insistence on an integral, relational vocation of protector.

In his social encyclical, Solicitudo rei socialis, St John Paul II spoke of the need to respect the constituent and inter-related elements of the natural world: “One cannot use with impunity the different categories of beings…animals, plants, the natural elements – simply as one wishes, according to one’s own economic needs. On the contrary, one must take into account the nature of each being and of its mutual connectio n in an ordered system, which is precisely the cosmos.”

n in an ordered system, which is precisely the cosmos.”

Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI also had this point as a central theme in his teaching. Some called him the ‘Green Pope’ because of the priority he gave to concern over our destruction of nature. He echoed the call of St John Paul II to “change our way of life… [to] eliminate the structural causes of global economic dysfunction, and to correct models of growth that seem incapable of guaranteeing respect for the environment and for integral human development.”

Pope Benedict’s message for the 43rd World Day of Peace in 2010 was abundantly clear: “The book of nature is one and indivisible; it includes not only the environment but also individual, family and social ethics. Our duties towards the environment flow from our duties towards the person, considered both individually and in relation to others.”

In Caritas in Ve ritate, he famously called contemporary society to a serious review of its lifestyle, which is so often prone to hedonism and consumerism, regardless of their harmful consequences.

ritate, he famously called contemporary society to a serious review of its lifestyle, which is so often prone to hedonism and consumerism, regardless of their harmful consequences.

What is needed, he said, is an effective shift in mentality which can lead to the adoption of “new lifestyles” in which the quest for truth, beauty, goodness and communion with others for the sake of common growth are the factors which determine consumer choices, savings and investments.

It is such integral ecology that Pope Francis took up, in eminently pastoral terms, in his inaugural homily.

He does so again in his Apostolic Exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium when he calls all people to a new solidarity, “the creation of a new mind-set which thinks in terms of community and the priority of the life of all over the appropriation of goods by a few” (n.188).

![]() II Second Principle: care for creation is a virtue in its own right

II Second Principle: care for creation is a virtue in its own right

In an airplane interview while returning from Korea last August, the Holy Father said that one of the challenges he faces in his encyclical on ecology is how to address the scientific debate about climate change and its origins.

Is it the outcome of cyclical processes of nature, of human activities (anthropogenic), or perhaps both? But as Cardinal Turkson underlined, what is not contested is that our planet is getting warmer.

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has undertaken the most comprehensive assessment of climate change. Its November 2014 Synthesis Report was as stark as it was challenging. In the words of Thomas Stocker, the co-chair of the IPCC Working Group I: “Our assessment finds that the atmosphere and oceans have warmed, the amount of snow and ice has diminished, sea level has risen and the concentration of carbon dioxide has increased to a level unprecedented in at least the last 800,000 years.”

Yet even the compelling consensus of over 800 scientists of the IPCC will have its critics and its challengers, Cardinal Turkson acknowledged. For Pope Francis, however, this is not the point. For the Christian, to care for God’s ongoing work of creation is a duty, irrespective of the causes of climate change. To care for creation, to develop and live an integral ecology as the basis for development and peace in the world, is a fundamental Christian duty.

“As Pope Francis put it in his morning homily at Santa Marta on 9 February, it is wrong and a distraction to contrast ‘green’ and ‘Christian’. In fact, “a Christian who doesn’t safeguard creation, who doesn’t make it flourish, is a Christian who isn’t concerned with God’s work, that work born of God’s love for us.”

“As Pope Francis put it in his morning homily at Santa Marta on 9 February, it is wrong and a distraction to contrast ‘green’ and ‘Christian’. In fact, “a Christian who doesn’t safeguard creation, who doesn’t make it flourish, is a Christian who isn’t concerned with God’s work, that work born of God’s love for us.”

He said the Pope was affirming a truth revealed in the first pages of Sacred Scripture, specifically where humankind is placed in the Garden by the Creator to “till it and keep it” (Gen 2:15).

“These concepts of ‘tilling’ and ‘keeping’ involve a vital and reciprocal relationship between humanity and the created world.

When Pope Francis says that destroying the environment is a grave sin; when he says that it is not large families that cause poverty but an economic culture that puts money and profit ahead of people; when he says that we cannot save the environment without also addressing the profound injustices in the distribution of the goods of the earth; when he says that this is “an economy that kills” – he is not making some political comment about the relative merits of capitalism and communism. He is rather restating ancient Biblical teaching.

He is pointing to the fact that being a protector of creation, of the poor, of the dignity of every human person is a sine qua non of being Christian, of being fully human. He is pointing to the ominous signs in nature that suggest that humanity may now have tilled too much and kept too little.

That our relationship with the Creator, with our neighbour, especially the poor, and with the environment has become fundamentally “un-kept”, and that we are now at serious risk of a concomitant human, environmental and relational degradation.

![]() III Third principle: We must care for what we cherish and revere

III Third principle: We must care for what we cherish and revere

While binding regulations, policies, and targets are necessary tools for addressing poverty and climate change, they are unlikely to prove effective without moral conversion and a change of heart according to Cardinal Turkson.

He noted the many attempts in recent years to implement international agreements on development goals, carbon emission targets and climate change limits, with varying degrees of success. Citing the Millennium Development Goals, he highlighted that they have only achieved partial success, with half remaining unfulfilled.

“For instance, between 1.2 and 1.5 billion people are still mired in ‘extreme poverty’. Global inequalities continue to widen. Sub-Saharan Africa has the second highest rate of economic growth in the world (after developing Asia). Nevertheless, the region remains locked in a negative cycle of poverty and underdevelopment, with development aid shifting away from some of the poorest countries. The wealth of the top 1% has grown 60% in the last twenty years, and it continued to grow through the global economic crisis,” the President of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace outlined.

“For instance, between 1.2 and 1.5 billion people are still mired in ‘extreme poverty’. Global inequalities continue to widen. Sub-Saharan Africa has the second highest rate of economic growth in the world (after developing Asia). Nevertheless, the region remains locked in a negative cycle of poverty and underdevelopment, with development aid shifting away from some of the poorest countries. The wealth of the top 1% has grown 60% in the last twenty years, and it continued to grow through the global economic crisis,” the President of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace outlined.

He also highlighted that despite the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change signed in Rio in 1992 and subsequent agreements, global emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) continue their upward trend, almost 50 percent above 1990 levels.

“The concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere has reached a level last seen 3 million years ago – when the planet was significantly warmer than it is today. Millions of hectares of forest are lost every year, many species are being driven closer to extinction, and renewable water resources are becoming scarcer.”

He said the list could go on. “Certainly international agreements are important, they can help. But they are not enough in themselves to sustain change in human behaviour. As St John Paul II put it, we require an ‘ecological conversion’, a radical and fundamental change in our attitudes to creation, to the poor and to the priorities of the global economy.”

Referring to the Pope’s choice of the name Francis, he said St Francis of Assisi is an example par excellence of a lived and integral ecology. “In fact, St Pope John Paul II had declared him the patron saint of those who promote ecology. His love for creation, for creatures and for the poor, are one, they form an integral whole.”

Referring to the Pope’s choice of the name Francis, he said St Francis of Assisi is an example par excellence of a lived and integral ecology. “In fact, St Pope John Paul II had declared him the patron saint of those who promote ecology. His love for creation, for creatures and for the poor, are one, they form an integral whole.”

By pointing the faithful towards the example of St Francis of Assisi, Pope Francis teaches the world that the ancient wisdom, insights and values of religious faith, most notably the tradition of Catholic Social Doctrine, can contribute something of value to the search for sustainable development, based on an integral ecology. Genuine ‘ecological conversion’ involves the whole person, he explained.

“This is why the cultural trend of relegating religious language, religious motivation and religious faith to the sphere of the purely private and personal undermines a vital and powerful source of meaning and action in the common effort to address both climate change and sustainable development,” he challenged.

He added that the Judaeo-Christian insight into creation can transform our relationship from that of remote observers or technical managers of nature, to that of “brother and sister”, of nurturer and protector of all.

![]() IV Fourth principle: the call to dialogue and a new global solidarity

IV Fourth principle: the call to dialogue and a new global solidarity

Fourthly, for Pope Francis, integral ecology, as the basis for justice and development in the world, requires a new global solidarity, one in which everyone has a part to play and every action, no matter how small, can make a difference.

Fourthly, for Pope Francis, integral ecology, as the basis for justice and development in the world, requires a new global solidarity, one in which everyone has a part to play and every action, no matter how small, can make a difference.

During World Youth Day celebrations in Brazil in July 2013, this call to solidarity became most explicit in his address to Varginha, a favela community.

Pope Francis noted that the rich could learn much from the poor about solidarity: “I would like to make an appeal to those in possession of greater resources, to public authorities and to all people of good will who are working for social justice: never tire of working for a more just world, marked by greater solidarity…”

“The culture of selfishness and individualism that often prevails in our society is not what builds up and leads to a more habitable world: it is the culture of solidarity that does so, seeing others not as rivals or statistics, but brothers and sisters.”

As this year’s Drop in the Ocean campaign by Trócaire implies, and as the Pastoral Letter of the Irish Bishops’ Conference, The Cry of the Earth, points out, “Action at a global level, as well as every individual action which contributes to integral human development and global solidarity, helps to construct a more sustainable environment and therefore, a better world”

![]() Biog of Cardinal Peter Turkson:

Biog of Cardinal Peter Turkson:

The President of the Vatican’s high profile Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, Cardinal Peter Turkson, is the first Ghanaian ever to be made a cardinal. The 66-year-old was born in Wassaw Nsuta, a mining town in western Ghana, about 480kms west of the capital Accra.

The President of the Vatican’s high profile Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, Cardinal Peter Turkson, is the first Ghanaian ever to be made a cardinal. The 66-year-old was born in Wassaw Nsuta, a mining town in western Ghana, about 480kms west of the capital Accra.

Growing up, his family’s circumstances were humble. He shared a small wooden bungalow with his nine siblings and his parents; his mother was a Methodist and sold vegetables at the market to supplement his Catholic father’s income as a carpenter.

As a schoolboy, the young Peter Kodwo Appiah Turkson was a good student with a love of table tennis and the bass guitar, on which he strummed the songs of James Brown, according to his childhood friend Dunhill Pawosey.

He studied for the priesthood at St Teresa’s Seminary in the village of Amisano and Pedu before attending St Anthony-on-Hudson Seminary run by Conventual Franciscans in Rensselaer in New York, where he obtained a degree in theology. That’s why when he speaks in English, he has a gentle Kofi Annanesque delivery but also a slight American ‘twang’ – four years of study in the US have left their mark he joked on a recent visit to Ireland.

Fr Turkson was ordained to the priesthood in July 1975 and spent a year teaching in a minor seminary in Ghana before he was sent to Rome in 1976 to study scripture at the Pontifical Biblical Institute.

In 1980, he obtained a licentiate at the Biblicum and later he returned in 1987 to study for a doctorate.

In 1980, he obtained a licentiate at the Biblicum and later he returned in 1987 to study for a doctorate.

In fact, he was completing his exegetical study of King Solomon’s dedication of the Temple, examining the king’s prayer that God hear the voice of the “foreigner, who is not of your people Israel” (1 Kings 8:41-43) when he got news of his appointment as archbishop of Cape Coast in 1992. He was just 43 years old.

In the ten years from when he received the red hat from St Pope John Paul II at the ailing pontiff’s last consistory in 2003, Cardinal Turkson participated in some of the most important events in the Church’s recent history.

He was one of the cardinal electors in the 2005 papal conclave which selected Pope Benedict XVI and the 2013 conclave which elected Pope Francis.

Considered a conservative and ‘papabile’, he was touted by the media in the immediate aftermath of Benedict XVI’s resignation as likely to become Africa’s first pope.

An intellectual who is both gracious and a bit of a polyglot, he has been perceived as a rising star from the peripheries and this was crowned by Benedict XVI’s appointment of him as president of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace in 2009.

A happy choice for the man whose name is ‘Kodwo’ meaning Monday, that day of the week in Ghana associated with peace.

A happy choice for the man whose name is ‘Kodwo’ meaning Monday, that day of the week in Ghana associated with peace.

Justice and Peace is one of the Dicasteries of the Holy See that was created after the Second Vatican Council “to stimulate the Catholic community to foster progress in needy regions and social justice on the international scene”.

It’s more progressive agenda is perhaps reflected by the fact that its Undersecretary is the Italian, Dr Flaminia Giovanelli, the highest-ranking laywoman to work in the Curia.

Speaking in St Brigid’s parish on the theme ‘Pope Francis and the Joy of the Gospel: The Social Dimension’, the Cardinal said he was “particularly pleased” to have the opportunity to make his first visit to Belfast.

Speaking in St Brigid’s parish on the theme ‘Pope Francis and the Joy of the Gospel: The Social Dimension’, the Cardinal said he was “particularly pleased” to have the opportunity to make his first visit to Belfast.

“For many years, images of violent conflict have flashed across the world from this divided city,” he commented and said it was “a great joy to witness at first hand the enormous efforts being made in the search for reconciliation and peace among the people of this city and between the islands of Great Britain and Ireland”.

Recalling his own involvement in the National Peace Council of Ghana from 2006-2010 which brokered pre- and post-electoral peace processes, Cardinal Turkson said the journey to peace “rarely travels along a fast road” and that Northern Ireland was likely to face many other challenges along the way.

“It is more likely to meander down narrow paths and double back over difficult terrain. It much requires God’s help.”

Referring to the peace process, he recognised that there are on-going tensions about symbols of identity and parades. “How do we accommodate for differences while we pursue the greater common good?” he asked and paid tribute to the combined efforts of many in public, civic and ecclesiastical life.

Northern Ireland, the high profile Vatican prelate said, had managed to keep moving towards peaceful co-existence and political stability.

“I therefore welcome this opportunity to express the continued solidarity and prayerful support of the Holy See in your efforts to build, upon the agreements already achieved, a truly reconciled and therefore peaceful future for all.”

He added that the rest of the world, particularly those parts that continue to wrestle with long-running conflict, look at Northern Ireland’s journey towards peace with great interest and hope.

Recalling Saint John Paul II’s visit to Ireland in 1979, Cardinal Turkson said the Polish Pontiff had made a particular point of paying homage “to the countless men and women” who over the years had stepped beyond the comfort and security of their own community and traditions “to walk the path of reconciliation and peace”, often at great personal or political risk to themselves.

He said this going out to the peripheries was at the very heart of Pope Francis’s vision for the church as evidenced in his bringing together of Israeli and Palestinian leaders for a joint service of prayer for peace and mutual understanding in the Vatican as well as his powerful vigil of prayer for peace and an end to the use of chemical weapons in Syria.

Archbishop Diarmuid Martin, Mullingar catechists Helen Kieran and Antoinette Shaw, Cardinal Peter Turkson.

In addressing how secularism is relegating Christianity and religious faith to the private sphere, the Ghanaian prelate underlined the importance of supporting Catholics who enter into politics and those called as public servants.

“I was very struck by the fact that when Saint John Paul II visited Ireland in 1979, he spoke of those ‘called to the noble vocation of politics’.

This is a theme which the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace is studying with a view to articulating the vocation of the political leader: how to give greater support and guidance to those Catholics who are called to witness to the joy and transforming power of the Gospel as elected representatives or public servants.”

He said it would challenge the view that a Catholic politician can somehow publicly or privately disregard the teaching of the Church while still claiming to be a committed and informed member of the Church.

Concluding his talk in Belfast, Cardinal Turkson invoked St Brigid – Mary of the Gael and patroness of Ireland. Saying he was conscious that he had come to a country which, since the time of St Patrick, has given much to the rest of the world in terms of “proclaiming the Gospel in a missionary tone”, he praised this living flame of missionary faith.

In the year marking the 1400th anniversary of the death of St Columbanus, Cardinal Turkson said the Irish monk and his monastic companions who left from Bangor with him, not far from the shores of Belfast Lough, had “sowed the seeds” of the “great peace project we know today as the European Union”.