Summary Dominic Collins was a big man in every way. A soldier of fortune in the Catholic armies of Europe, joined the Jesuits in Santiago de Compostela, sent back to Ireland in 1601 with army of Spaniards going to Kinsale, eventually captured and put to death for his faith.

Desmond Forristal tells his story.

Dominic was born into a leading Catholic family in Youghal, Co Cork in 1566. Both his father and his brother served as mayor in the town. Two friaries, Franciscans and Dominicans, flourished in the town beside the parish church. In 1577 two Irish Jesuits, Fathers Charles Lea and Robert Rochford, settled in the town, setting up a grammar school and organising classes in Christian doctrine for adults. Dominic may have attended this school. Later in life he said he learned some Latin as a boy, but admitted having forgotten it.

Dominic was born into a leading Catholic family in Youghal, Co Cork in 1566. Both his father and his brother served as mayor in the town. Two friaries, Franciscans and Dominicans, flourished in the town beside the parish church. In 1577 two Irish Jesuits, Fathers Charles Lea and Robert Rochford, settled in the town, setting up a grammar school and organising classes in Christian doctrine for adults. Dominic may have attended this school. Later in life he said he learned some Latin as a boy, but admitted having forgotten it.

Local people acknowledged the rule of Queen Elizabeth, but were reluctant to accept Anglicanism as the new religion. The pope, not the Queen, was the head of their Church. In 1579 the Catholic Earl of Desmond led a rebellion against the Queen. The people of Youghal, though sympathetic to his religious aims, did not join the rebellion, so he seized and the town and destroyed many of its buildings. The Jesuit school closed.

Soldier of Fortune

When the Desmond Rebellion was crushed, there was little else for a young Catholic man with ambition like Collins but to seek a career on the continent. He had grown up tall, strong and handsome. Sailing to France, he enlisted in the army of the Duke of Mercoeur, fighting for the Catholic League against the Huguenots in Brittany. For nine years, he served with distinction and rose through the ranks. His greatest moment came when he captured a strategic castle at Lapena and was appointed military governor of the region.

When the Desmond Rebellion was crushed, there was little else for a young Catholic man with ambition like Collins but to seek a career on the continent. He had grown up tall, strong and handsome. Sailing to France, he enlisted in the army of the Duke of Mercoeur, fighting for the Catholic League against the Huguenots in Brittany. For nine years, he served with distinction and rose through the ranks. His greatest moment came when he captured a strategic castle at Lapena and was appointed military governor of the region.

As governor he showed himself to be as honest as he was brave. When the Catholic League began to disintegrate, Henry IV of France offered him 2,000 ducats to hand over the castle, but he refused the bribe. Instead he gave the castle and its surrounding territory to the Spanish general, Don Juan del Aguila, who represented the devoutly Catholic King of Spain, Philip II. He then set out for Spain with a letter of recommendation from del Aguila, and was granted a pension of 25 crowns a month by the King.

Jesuit brother

Disenchanted with soldiering, even though King Philip II had placed him in the garrison at La Coruña on Spain’s Bay of Biscay, in 1598 he met a fellow Irishman, a Jesuit priest called Father Thomas White, to whom he confided his desire to join the Jesuits and serve as a brother.

Father White had come to Spain from Clonmel and in 1592 founded the Irish College at Salamanca for the education of young Irishmen, especially those who wanted to study for the priesthood. Soon afterwards he joined the Society of Jesus. There were many Catholic Irishmen living in Spain at the time, seeking the education and the careers that were no longer open to them at home. It was in his capacity as chaplain to the Irish community that Fr White met Dominic. He left this description of their first meeting which took place in the spring of 1598:

I went to the coast to hear the confessions of Irish soldiers in the fleet which was stationed there during Lent. Among them I met this officer, Dominic Collins. When I spoke to him he gave thanks to our Lord for meeting a priest who was a member of the Society of Jesus and a fellow countryman. He told me that for more than ten months he was unable to feel any joy or inward peace by reason of a struggle with our Lord who was urging him to choose a different walk in life and leave the world and its vanities. He told me he had said this to friars of different orders to whom he made his confession during this time, and that they had offered to give him the habit of their order and to make him a priest or religious, according as he might wish; that he had no inclination or desire for what the friars offered him, but that when he heard I was a member of the Society of Jesus he felt an inward joy which he could not account for or explain.

Fr White was impressed by Dominic’s sincerity, but also pointed out some difficulties. Already in his thirties and with little formal education, he could not hope to become a Jesuit priest, and if he were accepted as a brother he would have to carry out the kind of duties he might think beneath his dignity as a high-ranking officer. Dominic was not in the least discouraged. He said he would do any work if only he were accepted by the Society. Fr White agreed to write about him to the Provincial.

The Jesuits were initially reluctant to accept him because they felt that a battle-hardened soldier would never be able to settle into religious life. Dominic bombarded the provincial with requests and was finally admitted to the novitiate in Santiago de Compostela in Northern Spain.

At Santiago the Jesuit College was struck by a plague. Seven of the community were infected and many others fled for fear of catching the awful disease. Collins stayed on and tended the victims for two months, nursing some of them back to health and comforting the others in their last hours. He had proved his worth and completed his novitiate without further question. A report sent to Rome by his superiors states that he was a man of sound judgment and great physical strength, mature, prudent and sociable, though inclined to be hot-tempered and obstinate.

Return to Ireland: Kinsale 1601

At this time Ireland was in turmoil. In Ulster Hugh O’Neill and Red Hugh O’Donnell were defying the power of the English crown and trying to call all Ireland into revolt. In 1601 King Philip III of Spain decided to send an army to help the Irish rebels. A number of bishops and priests travelled with the expedition including an Irish Jesuit, Father James Archer, who asked that Brother Collins be sent as his companion for the journey even though the priest had never met Collins. The two set sail on different vessels, however, which became separated during a storm. Collins’s ship had to return to La Coruña before finally reaching Ireland. He arrived on 1st December 1601 at Castlehaven, 30 miles from Kinsale, where the main part of the Spanish fleet was already ensconced.

A large English army under Lord Mountjoy had laid siege to Kinsale. Irish forces, including O’Neill and O’Donnell from the North and O’Sullivan Beare from West Cork, converged on the town. Dominic along with the Spanish soldiers in his ship travelled with O’Sullivan Beare, hoping to link up with Fr Archer there. The Irish army surrounded the English on the outside of the town while the Spanish faced the English from inside. The Irish attacked at dawn on Christmas Eve, but for reasons never fully understood, suffered a humiliating defeat, with no help from the Spaniards who remained within the town.

The Irish scattered. O’Neill and O’Donnell’s armies marched back northward while O’Sullivan Beare led his men back to the Beara peninsula. Dominic Collins accompanied them to Bearhaven, a deep, safe harbour sheltered by Beare Island from the Atlantic. Dunboy Castle, a small square fortress on the mainland overlooking Beare Island, its guns commanding the strait leading to the harbour, was the spot that O’Sullivan chose to make a last-ditch stand against the English. Dominic was joined here by Fr Archer, who had escaped from Kinsale. It was the first time he and Dominic had met.

O’Sullivan’s strategy was to pin down for as long as posssible the English army, now under the command of Sir George Carew, president of Munster. A picked garrison would hold the castle while O’Sullivan would attack the besiegers from the mountains on the mainland peninsula. This would give the other Irish chieftains time to regroup and keep resistance alive until the arrival of reinforcements which were expected to land shortly from Spain. The first part of the strategy worked, and the English forces were tied up there for six months after victory at Kinsale. They could not approach the castle by sea because of bad weather and O’Sullivan’s guerillas harrassed them in the mountains. The second part failed because the Spaniards never came.

The Siege of Dunboy Castle

Eventually on 6th June 1602 Carew had 4,000 English troops make an unexpected landing on a sandy beach just below the castle. Some of the Irish crossed the mountains to join O’Sullivan Beare on the north side of the peninsula, about twenty miles away. With them was Father Archer who subsequently set out for Spain seeking more aid. O’ Sullivan with his thousand men did not intervene and was later accused of callousness and cowardice. Possibly he still hoped for the Spanish troops which would have turned the balance in his favour.

Dunboy Castle

Inside the castle were 143 soldiers under the command of Richard McGeoghegan. As a religious, Dominic could not take part in the fighting but as a veteran of so many battles he could give bodily and spiritual assistance to the wounded and the dying. As a Jesuit religious he could keep before their eyes the cause for which they were fighting, their lands and their faith.

For ten days the English dug in around the castle and attacked, but were beaten back. Eventually on 17th June when their guns were in position, they bombarded the castle unremittingly. When the tower eventually fell, they rushed the breach but were driven back. The defenders fought bravely and towards evening retreated down into the crypt of the castle. As night was drawing on, the English dared not press further. They simply placed their flags on the castle ruins and waited to see what the morning would bring. But just after sunset a tall figure emerged from the crypt and made its way through the smoking rubble and over the piled-up corpses. Dominic, knowing how anxious Carew was to capture a Jesuit, hoped that by handing himself over he could negotiate an honourable cease-fire. But Carew refused to consider the proposal and ordered Dominic to be held prisoner.

Next day The English started firing on the ruins and into the crypt. It was clear to the defenders that Dominic’s peace attempt had failed. After a bitter siege, with huge casualties, the defenders surrendered. What was left of the castle was blown up. Of the seventy-three prisoners that survived Carew set aside three for questioning – Dominic Collins, Thomas Taylor, and an Irishman of noble birth, Turlough Roe MacSwiney. The rest were brought to the market-place and hanged, fifty-eight on that day, 18th June, and the remaining twelve four days later.

The ruins of Dunboy Castle can still be seen today on a small headland, facing Beare Island. Though grass has grown over the ruins and cows graze peacefully where so many men fought and died, three walls of the crypt survive and a part of the stone stairway. On one of the walls is a commemorative tablet with an inscription in Irish:

I gcuimhne na laoch do thuit i nDún Baoi

ar son tíre is creidimh Meitheamh 1602

Tógadh an leac so 22adh Meitheamh 1953.

Suaimhneas síorraí d’á nAnam.In memory of the warriors who fell in Dunboy

for fatherland and faith in June 1602

This tablet was erected 22 June 1952.

Eternal rest to their souls.

Interrogation

The three surviving prisoners were brought to Cork for interrogation. Taylor and MacSwiney were soon executed, as they had little to reveal. Collins, a Jesuit lately come from Spain, was thought to be a more promising prospect. Carew interrogated him at length on 9th July, and sent a long report to London on the result of the interrogation, but was forced to admit that it contained little of value. Dominic answered questions about his years in France and Spain and his return to Ireland, but nothing he said was of any military importance. There seemed no reason to postpone his execution any longer.

But Carew had other plans. He thought if he could persuade the Jesuit to renounce his allegiance to the Pope and embrace the new religion it would be a resounding propaganda victory. No effort was spared in the attempt to break Dominic’s resolution. We are told that he was savagely tortured, though the form of torture is not mentioned. He was promised rich rewards and high ecclesiastical office if he would accept the doctrines of Anglicanism. Ministers of religion were sent to persuade him of the error of his beliefs. Even some of his own family visited him, urging him to save his life by pretending a conversion which he could afterwards repudiate. He was in his middle thirties with much to live for. But he rejected all the offers, and chose a martyr’s death.

But Carew had other plans. He thought if he could persuade the Jesuit to renounce his allegiance to the Pope and embrace the new religion it would be a resounding propaganda victory. No effort was spared in the attempt to break Dominic’s resolution. We are told that he was savagely tortured, though the form of torture is not mentioned. He was promised rich rewards and high ecclesiastical office if he would accept the doctrines of Anglicanism. Ministers of religion were sent to persuade him of the error of his beliefs. Even some of his own family visited him, urging him to save his life by pretending a conversion which he could afterwards repudiate. He was in his middle thirties with much to live for. But he rejected all the offers, and chose a martyr’s death.

Execution

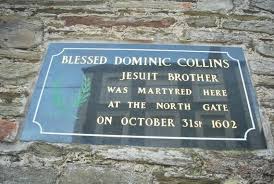

Taken to Youghal on 31st October 1602, he was marched by a troop of soldiers through the streets to the place of execution. It was the first time he had seen his home town in fifteen years. He wore the black gown of his order, which he had desired so long and loved so greatly. He knelt at the foot of the gallows and greeted it joyfully: “Hail, holy cross, so long desired by me!” Then he addressed the crowd in a mixture of Spanish, Irish and English, telling them that he had come to Ireland to defend the faith of the Holy Roman Church, which was the one true path to salvation and for which he was about to die. He was so cheerful that an English officer remarked, “He is going to his death as eagerly as I would go to a banquet”. Dominic overheard him and replied, “For this cause I would be willing to die not once but a thousand deaths”.

Taken to Youghal on 31st October 1602, he was marched by a troop of soldiers through the streets to the place of execution. It was the first time he had seen his home town in fifteen years. He wore the black gown of his order, which he had desired so long and loved so greatly. He knelt at the foot of the gallows and greeted it joyfully: “Hail, holy cross, so long desired by me!” Then he addressed the crowd in a mixture of Spanish, Irish and English, telling them that he had come to Ireland to defend the faith of the Holy Roman Church, which was the one true path to salvation and for which he was about to die. He was so cheerful that an English officer remarked, “He is going to his death as eagerly as I would go to a banquet”. Dominic overheard him and replied, “For this cause I would be willing to die not once but a thousand deaths”.

His words and demeanour so touched the crowd that the hangman refused to do his work. The soldiers eventually seized on a passer-by, a poor fisherman, and forced him to accept the office. He asked the victim for forgiveness, which Dominic gladly granted before mounting the ladder with the rope around his neck. Reciting a psalm, he had just reached the words “Into your hands I commend my spirit”, when the fisherman pulled away the ladder; and so he died.

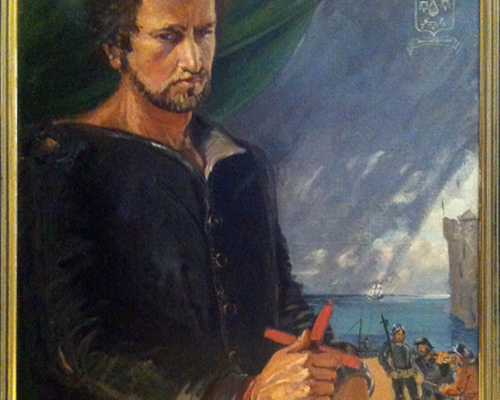

Left hanging on the gallows for several hours, the rope eventually broke and his body fell to the ground. Under cover of darkness local Catholics took him away and buried him reverently in a secret place. From that day he was venerated as a martyr in Youghal and his fame quickly spread throughout Ireland and parts of Europe. In the Irish Colleges of Douai and Salamanca the Jesuits showed his portrait. Many favours and cures were attributed to his intercession.

A martyr

It might be suggested that Dominic Collins’s execution was for political rather than religious reasons. Had he been hanged with the rest of the Dunboy garrison immediately after the siege, there could be some room for doubt. But he was not executed until more than four months later, and it was made clear to him that he could save his life if he renounced his religion. It was his choice to die as a martyr.

Today we know Dominic Collins only through the words of others, some friends, others enemies. No letters or writings of his own survive. Yet we feel he is someone we know well. His personality is still vivid after almost four hundred years.

A big man in every way – in height, in strength, in heart, in mind – he was at the same time capable of great gentleness and humility. A veteran soldier, who lived for nine years the rough life of the army camp, he kept through it all a strange innocence and holiness and goodness. A much-honoured officer, who had served under kings and generals, he was happy to kneel and scrub floors in honour of a greater king. In his life and in his death he remains one of the most attractive and lovable of all the Irish martyrs.

This is an edited version of the pamphlet written by Desmond Forristal and published by The Messenger in 1992.