– 24th July 2022 –

Gospel Text: Luke 11:1-13

vs.1 Once Jesus was in a certain place praying, and when he had finished one of his disciples said, “Lord, teach us to pray, just as John taught his disciples.”

vs.1 Once Jesus was in a certain place praying, and when he had finished one of his disciples said, “Lord, teach us to pray, just as John taught his disciples.”

vs.2 He said to them,

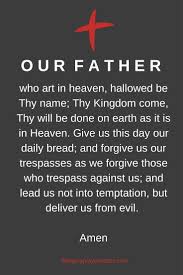

“Say this when you pray:

Father, may your name be held holy, your kingdom come;

vs.3 give us each day our daily bread, and forgive us our sins,

vs.4 for we ourselves forgive each one who is in debt to us.

And do not put us to the test.”

vs.5 He also said to them,

“Suppose one of you has a friend and goes to him in the middle of the night to say,

‘My friend, lend me three loaves,

vs.6 because a friend of mine on his travels has just arrived at my house and I have nothing to offer him’;

vs.7 and the man answers from inside the house, ‘Do not bother me. The door is bolted now, and my children and I are in bed; I cannot get up to give it you.’

vs.8 I tell you, if the man does not get up and give it him for friendship’s sake, persistence will be enough to make him get up and give his friends all he wants.

vs.9 So I say to you:

Ask, and it will be given to you;

search, and you will find;

knock, and the door will be opened to you.

vs.10 For the one who asks always receives; the one who searches always finds;

the one who knocks will always have the door opened to him.

vs.11 What father among you would hand his son a stone when he asked for bread? Or hand him a snake instead of a fish?

vs.12 Or hand him a scorpion if he asked for an egg?

vs.13 If you then, who are evil, know how to give your children what is good, how much more will the heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him!”

*******************************************

We have four commentators available from whom you may wish to choose .

Michel DeVerteuil : A Trinidadian Holy Ghost Priest, director of the Centre of Biblical renewal .

Thomas O’Loughlin: He is on the theology faculty of Nottingham University

Sean Goan: Studied scripture in Rome, Jerusalem and Chicago and works with the Le Chéile Schools

Schools.

Donal Neary SJ: Editor of The Sacred Heart Messenger

*******************************************************

Michel de Verteuil

Lectio Divina The Year of Luke

www.columba.ie

General Textual Comments

Jesus’ teaching on prayer in this passage has many aspects. There is no need to look for an overall logic in the passage; just choose the aspect that touches you here and now.

Verse 1: the disciples ask Jesus to teach them how to pray.

Verses 2-4: the Lord’s prayer. As the introductory words indicate, the prayer was given not so much as a formula, but as a style of prayer. The following verses will help you identify what this style is.

Verses 2-4: the Lord’s prayer. As the introductory words indicate, the prayer was given not so much as a formula, but as a style of prayer. The following verses will help you identify what this style is.

The prayer here is Luke’s version, which is slightly different from the one we are accustomed to which comes mostly from Matthew 5:9-13.

Verses 5-8: this is a parable. As in last week’s meditation, discover what is for you the significant moment of the story; it will lead you to the word God has for you in this parable.

In verses 9 to 13, the parable is interpreted by Jesus, although as a teaching it can stand on its own. To get the full teaching in verses 9 and 10, you must take literally the word “always” repeated three times. There is a tendency to water it down, and as a result the message is lost.

Enter into the movement of verses 11 and 13, and the dramatic style of the teaching.

Scripture Reflections

“The modern world listens more willingly to witnesses than to teachers, and if it does listen to teachers, it is because they are witnesses.” ... Pope Paul VI, Evangelii Nuntiandi

Lord, remind us that the most effective way to teach others how to pray, is for them to find us praying, and when we are finished to ask us to teach them how we do it.

Lord, many people today are learning to pray in traditions that are foreign to us – …TM, yoga, Zen meditation., prayer in the spirit, prayers while moved by nature.

We pray that, as Jesus did for his disciples,

that his Church may hear the cry of its members asking to be taught how to pray.

“In this world monopoly, do we ever ‘pass go’ or do we ‘go straight to jail’?”…David Rudder, Trinidad Calypsonian

Lord, we thank you for moments of prayer when we find within ourselves a hope

that your name will be held holy and your kingdom come.

“When I give bread to the hungry, they call me a saint;

when I ask why the hungry have no bread, they call me a communist.” …Bishop Helder Camara

Lord, help us, when we pray for the coming of your kingdom, to ask for it in its entirety.

Keep us searching for the day when every one will have each day their daily bread,

when those in debt will be freed of all their indebtedness,

and poor people will no longer be put to the test of survival.

“We should let ourselves be brought naked and defenseless before God, without explanation, without theories, completely dependent upon his providential care, in dire need of the gift of his grace, his mercy and the light of faith.” …Thomas Merton

Lord, you have revealed yourself to us as friend, and that has been helpful.

But it could lead us to become complacent, as if you owe us favours.

So every once in a while we experience you as someone who gives us our daily bread

not from friendship but because we persist in knocking at your door.

Thank you, Lord.

“Prayer is the union of nothing with the Nothing.” …Augustine Baker, English mystic

Lord, forgive us that we have made prayer into a bargain,

where in exchange for our asking we receive your favours.

Bring us to that prayer which is merely knocking at a door that is already open,

searching in the dark for something that is already found.

Lord, we sometimes think we have to leave our experience to get close to you.

But Jesus taught us to start with what we have known.

So today, we thank you for those who love us,

friends, parents, spiritual guides, teachers,

the kind of people we know if ever we asked them for bread,

no way would they give us a stone,

or if we asked them for fish, no way would they hand us a snake,

and if we asked them for an egg, no way would they hand us a scorpion.

Lord, these people are good but their goodness cannot compare with yours.

**************************************

Thomas O’Loughlin

Liturgical Resources for the Year of Luke

www.Columba.ie

Introduction to the Celebration

We are assembled here, not as a bunch of individuals, but as distinct members of a single body. This is something that we recall in a special way today when we read a story about the first disciples asking to be taught how to prayer together. We are the people who can call God our Father, who gather now to thank him and praise his name, who gather to ask him for our daily needs, and who ask him to forgive us as we forgive others. We need to pause now and recall our need of forgiveness for ourselves, and Jesus’s call to us to forgive others.

We are assembled here, not as a bunch of individuals, but as distinct members of a single body. This is something that we recall in a special way today when we read a story about the first disciples asking to be taught how to prayer together. We are the people who can call God our Father, who gather now to thank him and praise his name, who gather to ask him for our daily needs, and who ask him to forgive us as we forgive others. We need to pause now and recall our need of forgiveness for ourselves, and Jesus’s call to us to forgive others.

Gospel Notes

This story of the disciples asking for a lesson in prayer methods is only found in Luke; in Matthew (6:9-13) the ‘Our Father’ given in the context of an instruction forming part of the Sermon on the Mount.

So the first point to note is that in our memories we combine this occasion in Luke, with the text that is found Matthew. We see this common memory harmonising the texts in many introductions to the ‘Our Father’ in the liturgy.

Second, the text here seems ‘simpler’ than that which known in the tradition or found in Matthew; and therefore cause we assume everything develops in a sequence from ‘simple’ to ‘complex’, it is often glibly stated that therefore this Lukan version is ‘more original’ or even ‘closer to the words of Jesus’. This often leads to attempts to derive the familiar from this one in Luke, and it is an endeavour that invariably calls for ever more subtle moves to seem convincing. The place to start is not with the written gospels — either Matthew or Luke but with the community of the church which preserved the memory of Jesus during those crucial early decades before papyrus and ink could freeze the shape of the memory.

That Jesus taught some prayer that was distinctive in its approach to God is certain, as all the evidence coheres that there was a common Christian prayer formula and that it addressed God as ‘father’. That this was taught orally can be observed two ways.

Firstly, the well-rounded cadences and doublets (e.g ‘thy kingdom come, thy will be done’) point to a text rounded off to allow for easy committal to memory.

Secondly, the prayer has some minor variations in the various languages and in the manuscripts, and these variations show that oral transmission was the norm and that scribes followed their memories rather than their exemplars when copying Matthew.

The most famous of these slight variations is the doxology (‘for the kingdom, the power and the glory are yours now and forever’) which was omitted in Latin. Moreover, we know that the prayer, in virtually the shape we know it, was part of the training of new Christians before the time of our gospels: we find it in the Didache (but with one or two tiny changes which prove that the scribe was neither copying from memory or from Matthew). So we can conclude that before 70 AD this prayer in our familiar form was being learned by heart as part of the basic formation of every Christian.

Since it was such a basic element of the Didache (the training), it had to have a place in the kerygma (the preaching). Consequently, Matthew incorporated it into his most formal sermon exactly as it was recited in Greek in the churches in which he preached. Luke, however, opted to explain its importance with an origin story, and either knowing or recognising that it was well smoothed for memory based recitation, gave it a more archaic feel in his text. His construction — which has never been a reciting text anywhere — is therefore the first commentary on the prayer in so far as his text highlights what Luke saw as its most important features.

He then takes the opportunity to present some other teaching on prayer and the Father’s answering of prayer. First, he has the parable of the friend at midnight (11:5-8) — which is only found in Luke — which contrasts God’s concern with humanity with what one could expect from even base motives. Second, he has the statements on how the Father will answer those who ask for their needs. The interesting difference here with Matthew (7:11) is that while in Matthew the Father gives good things to those who ask him, here the Father gives the Holy Spirit to those who ask him. This fits with Luke’s overarching theology that it is the Spirit who dwells in, gives life to, and directs the church.

Homily Notes

1. This is a day when we really must learn from our history as the community founded on Jesus.

2. The written gospels that we treasure came into their written form in the last third of the first century. Mark was probably written in the late 60s, John in the 90s, and very probably Matthew and Luke sometime in between. There are many subtle arguments moving the dates a bit this way or bit that way, but this is a broad consensus, and does for our purposes. The key fact is that the written gospels are not only at least a generation after the first disciples – a generation being about 25 years – but they are in the different cultural setting of the Hellenistic cities rather than rural Palestine.

3. Now we can ask a key question: was it a book or books that kept the people together and gave them identity during these early years, or was it something else? The simplistic answer is to think of Christians as, to use an oft-repeated but wholly inappropriate phrase, ‘people of the book‘: so the key to Christian identity is that they accept ‘The Bible’ or ‘The Gospels‘ or some such set of writings. But Jesus is the only religious leader in history that. never wrote a book or dictated a book or even ordered a book to be written (writing in sand is hardly a good example of a desire for written records!).

4. What kept the community in being was its regular practices as a community and its memories recalled in community. To be a Christian is to be a member of a group, the community of the People of God, not to be just one more individual who buys into a philosophy or a spirituality.

5. How can we find out about these key practices? We can see them in three ways:

First,· we see them in a wonderful little guide for training new members which predates our written gospels and is given the rather off-putting title of The Training (the Didache). It is wonderful as it tells us directly what they had to do as a group.

Second, we see these practices referred to now and again in the letters that are in the New Testament, most of which predate our gospels.

Third, we see strange echoes of the practices in our gospels – they are ‘strange echoes’ as they usually are presented as an event which the first hearers of gospels would immediately see as the ‘original event’ that is the background and authorisation for what they are actually doing.

6. So what were these key practices? The first, and most important practice, was that they gathered each week as a group and the groups were probably no more than 25-50 people in size – and ate together the meal of the Lord. In the midst of a proper community meal, they thanked the Father for sending his Son to gather up the scattered flock of Israel and celebrated this re-gathering ‘Jesus-style’ by each getting his/her share in the one loaf and then each drinking from a single cup of blessing as they all had a single life-force surging through their veins. At this gathering they recalled the memory of Jesus and welcomed new members through baptism. This practice would become our Sunday Eucharist – the actual meal disappeared, and the memories were fixed by being written down. Over the centuries there have been other changes that have made the basic facts of eating and drinking less obvious, but one can still make out the pattern.

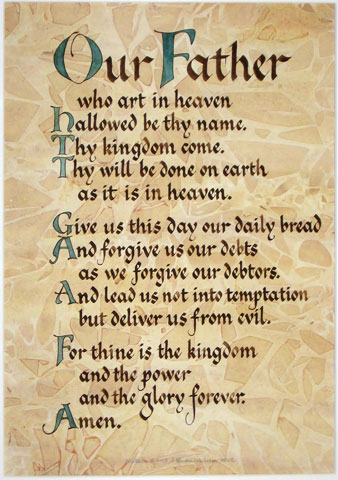

7. During the rest of the week they had fixed community practices. Fasting on Wednesdays and Fridays, and giving to charity were the two material practices of prominence. We see this given an ‘echo’ in the gospels in scene when Jesus tells the disciples to fast but not show off that you are fasting, to give alms but not ostentatiously, and to pray but not where everyone will see you (Mt 6). There was also a practice that was carried out each day: three times each day they recited the prayer we call the ‘Our Father’. This was done probably at morning, noon, and in the evening. It is this practice that is being given an origin point and’ authorisation’ in the words of Jesus himself, and a specific purpose, in today’s gospel reading.

7. During the rest of the week they had fixed community practices. Fasting on Wednesdays and Fridays, and giving to charity were the two material practices of prominence. We see this given an ‘echo’ in the gospels in scene when Jesus tells the disciples to fast but not show off that you are fasting, to give alms but not ostentatiously, and to pray but not where everyone will see you (Mt 6). There was also a practice that was carried out each day: three times each day they recited the prayer we call the ‘Our Father’. This was done probably at morning, noon, and in the evening. It is this practice that is being given an origin point and’ authorisation’ in the words of Jesus himself, and a specific purpose, in today’s gospel reading.

8. There is a strange aspect to this prayer that we usually miss when we say it during our Eucharists. It is the prayer of a group even when someone says it privately: it is a prayer to ‘Our Father, … give us this day … forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us, and lead us not, but deliver us from .. .’ What this tells us is that in those very first generations even when the group had not gathered together, the individuals had such a common sense of being part of the People of God, that they saw the fact that they were all praying at the same time (even if the individuals were physically apart) meant that they were offering a single group prayer. At morning, noon, and evening, even when alone, the Christians prayed as the single body of Christ to their Father.

9. This need for prayer at fixed times, and indeed to recite the Our Father, continued as part of the Liturgy of the Hours but this (with odd exceptions) is now something confined to ‘professional religious people.’ (You could show a volume of the Breviary as a visual aid at this point.) And, in any case, this is a far too cumbersome prayer for someone racing to get out in the morning, get the kids out, and get everything else done. However, saying the ‘Our Father’ – the bedrock of regular Christian prayer – is not too difficult: it does not require formally sitting or standing, it does not need so much time that a household needs to be ordered around the prayer, and it does not need a book.

9. This need for prayer at fixed times, and indeed to recite the Our Father, continued as part of the Liturgy of the Hours but this (with odd exceptions) is now something confined to ‘professional religious people.’ (You could show a volume of the Breviary as a visual aid at this point.) And, in any case, this is a far too cumbersome prayer for someone racing to get out in the morning, get the kids out, and get everything else done. However, saying the ‘Our Father’ – the bedrock of regular Christian prayer – is not too difficult: it does not require formally sitting or standing, it does not need so much time that a household needs to be ordered around the prayer, and it does not need a book.

10. Many Christians have today lost three precious understandings.

First, Christians have, to a large extent, lost the sense of the importance of formal prayer at regular times. Yet all human experience of religion – just look at the regular prayer times in Islam – not to mention our experience from the very first days of the church shows us that regular formal prayer is essential to preserve our sense of God.

First, Christians have, to a large extent, lost the sense of the importance of formal prayer at regular times. Yet all human experience of religion – just look at the regular prayer times in Islam – not to mention our experience from the very first days of the church shows us that regular formal prayer is essential to preserve our sense of God.

Second, Christians have often lost the sense that when we pray as Christians it is not my prayer and your prayer, but our prayer in Jesus. The sense of a common time uniting separated people is something that used to be reinforced by the Angelus Bell just as in Islam it is done by the voice of the muezzin, but we need to recall that when we prayer simultaneously we are praying as one body and I pray at this time to join my prayer with that of the body. Praying simultaneously is a non-computer-based ‘virtual community’.

Third, to be a Christian is to be a disciple, a disciple is one who learns over time and takes on the practices, the discipline, of the master. The master prayed regularly – as we hear about Jesus in today’s gospel- so must we.

11.A recovery of the practice of everyone saying the ‘Our Father’ morning, noon, and evening is the basis of a renewal programme for the whole church, that does not need a single meeting or handbook to get it started.

********************************************

Sean Goan

Let the Reader Understand

www.Columba.ie

Gospel Notes

Staying with the important theme of prayer, this week’s extract from Luke brings the teaching on prayer that accompanied the giving of the Our Father. In Luke, Jesus teaches this prayer because the disciples have asked for his help. The form of the prayer is the short one, as opposed to the longer version in Matthew which was adopted by the church as the version for use in the liturgy. In its short form we see even more clearly how this simple prayer has all that we need. We praise God as Father, we acknowledge that we want what he wants and that we trust him to look after us. We also recognise our need for forgiveness and our willingness to forgive. Finally we ask that in the life of faith we will not have to endure anything that would cause us to lose that faith. In what follows, Jesus uses the images of the unwilling friend and the caring parent to make us think about the relationship with God that should lie behind our prayer. God is the loving Father and in giving us the Holy Spirit he is holding back nothing.

Reflection

Today’s gospel is about prayer and in it Jesus encourages his followers to persevere in prayer and not to lose heart. The unanswered request and the door that remains shut are not unusual experiences for people who pray. Indeed we can be left wondering why our prayers are not answered. Is it because we lack faith or worse still because of our sins?

At such times we need to remember that Christian prayer is not about magic nor is it an elaborate heavenly lottery. Being baptised means that we share in the dying and rising of Christ, not just once but many times on our way home to the Father. Prayer teaches us about what is really important and, while it does not always take away our pain, through it we can come to understand a little better how and where God is at work in our lives.

******************************************************

4. Donal Neary S.J.

Gospel reflections for Year C: Luke

www.messenger.ie/bookshop

Trust in prayer

Often I pray to St Anthony and I find what I was looking for. I can’t understand why but it brings up the question of praying for what we want and need. People pray hard for an intention; some pray for ages and are answered, some are not.

We often pray for what may be outside God’s control: that someone may give up drink, when the person may not want to; that children will be kept safe on the roads, but they are killed or injured with the careless and dangerous driving of someone else, maybe under addictive influence.

We are encouraged always to pray with hope and persistence, believing that we always get something. In the asking is the receiving, and we never leave prayer worse off than when we began.

For any time we give to prayer, we get something. We are transformed. St Ignatius speaks of the effect of prayer – an increase in faith, hope and love. We may not get the specific intention but we always get the Holy Spirit. I have never left prayer the poorer than when I began. In the knocking at the door itself something is opened. In asking and seeking we get something. The first gift of prayer is the love of God. Other gifts follow.

Prayer increases our trust in God, that he wants our good and is with us in love.

So we pray for what we need and then leave the prayer with God, to be answered as he can. This is one of the greatest faiths of all.

Our Father,

holy be your name,

your kingdom come and

will be done within me and

in earth and heaven.

***************************