Summary: These forty men and women of England and Wales, martyred between 1535 and 1679, were canonised in Rome by Pope Paul VI on 25th October 1970. Each has their feast day but they are remembered as a group on 25th October.

Patrick Duffy tells their story.

Introduction

When King Henry VIII, after his break with Rome, proclaimed himself supreme head of the Church in England and Wales, Catholics felt that he had usurped a supremacy in spiritual matters that belonged only to the Pope. While they wished to remain loyal subjects of the Crown as the legitimately constituted authority, they refused for reasons of conscience to recognise the “spiritual supremacy” of the King. When the Act of Supremacy was passed in 1534, it quickly led many having to face a serious dilemma and even death rather than act against their conscience and deny their Catholic faith. It is important from the ecumenical point of view to note that these deaths were not the result of internal struggles between Catholics and Anglicans. It was rather that those who died were not willing to submit to what they saw was an illegitimate claim of the State.

When King Henry VIII, after his break with Rome, proclaimed himself supreme head of the Church in England and Wales, Catholics felt that he had usurped a supremacy in spiritual matters that belonged only to the Pope. While they wished to remain loyal subjects of the Crown as the legitimately constituted authority, they refused for reasons of conscience to recognise the “spiritual supremacy” of the King. When the Act of Supremacy was passed in 1534, it quickly led many having to face a serious dilemma and even death rather than act against their conscience and deny their Catholic faith. It is important from the ecumenical point of view to note that these deaths were not the result of internal struggles between Catholics and Anglicans. It was rather that those who died were not willing to submit to what they saw was an illegitimate claim of the State.

Persecution against Catholics

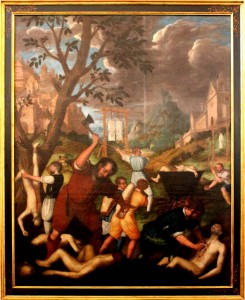

The martyrdoms involving the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales span the years from 1535 to 1679. Four distinct waves of persecution are discernible.

The first wave followed the passing of the First Act of Supremacy (November 1534) when Henry VIII broke with Rome and suppressed the monasteries. John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, and Henry’s former chancellor, Sir Thomas More, were executed in 1535 along with a number of religious.

The second wave came after 1570 when Pope Pius V, believing that Queen Elizabeth I as the daughter of Anne Boleyn was illegitimate and had no right to the throne of England, issued a papal bull Regnans in excelsis excommunicating her and absolving all her subjects from allegiance to her and her laws. This was a real dilemma for Catholics especially if they were asked the “bloody question”: if there was an invasion from the Pope, which would you support – Rome or England? The numbers of Jesuits coming in from the continent were seen as a real threat to the Queen and the realm. In 1581 an Act was passed that made it treason to withdraw English subjects from allegiance to the Queen or her Church and in 1585 the entrance of Jesuits into the country was prohibited by law. A number of Jesuits, secular priests and lay men and women were executed at this time.

The second wave came after 1570 when Pope Pius V, believing that Queen Elizabeth I as the daughter of Anne Boleyn was illegitimate and had no right to the throne of England, issued a papal bull Regnans in excelsis excommunicating her and absolving all her subjects from allegiance to her and her laws. This was a real dilemma for Catholics especially if they were asked the “bloody question”: if there was an invasion from the Pope, which would you support – Rome or England? The numbers of Jesuits coming in from the continent were seen as a real threat to the Queen and the realm. In 1581 an Act was passed that made it treason to withdraw English subjects from allegiance to the Queen or her Church and in 1585 the entrance of Jesuits into the country was prohibited by law. A number of Jesuits, secular priests and lay men and women were executed at this time.

The third wave of persecution followed the failed Gunpowder Plot in 1605. This was a somewhat unwise attempt by a number of Catholics to kill James I in a single attack by blowing up the House of Parliament during the ceremony of the State opening.

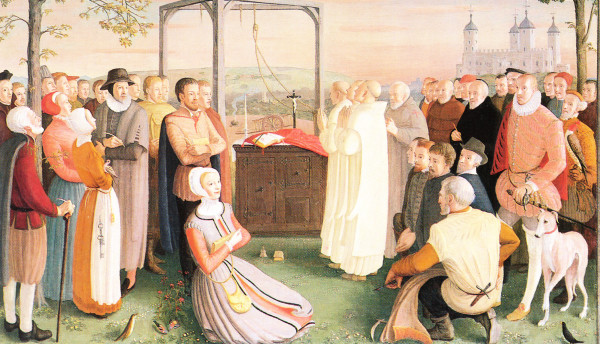

On 19 June 1535, Sebastian Newdigate, William Exmew and Humphrey Middlemore, monks of the Carthusian Order of London Charterhouse, were hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn.

The final wave came in 1678 following the so-called “Popish Plot” created by the infamous Titus Oates. Oates had been twice expelled from Jesuit colleges on the continent and was refused admission as a novice. He spread the rumour that the Jesuits in collusion with the Pope were plotting to overthrow King Charles II and make England a Catholic country again. The very rumour of a plot was enough to stir a new persecution of Catholics.

The History of the cause

In 1850 when the Catholic hierarchy of England and Wales was reconstituted, the cause of about 300 martyrs was introduced at Rome. Oliver Plunkett was among these at that time. Almost 200 of these were beatified by Leo XIII and Pius XI. Cardinal John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, and Henry VIII’s chancellor, Sir Thomas More, were canonised in 1936.

In the Consistory of 18th May 1970, Pope Paul VI consulted the cardinals and announced that he would canonise the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales on 25th October 1970. The forty canonised that day were considered, after More and Fisher, the most representative from the original list of almost three hundred. Each of these forty martyrs has their own day of memorial, but are remembered as a group on 25th October.

The Group of Forty

3 Carthusians:

Augustine Webster d.1535

John Houghton 1486-1535

Robert Lawrence d.1535

1 Augustinian friar John Stone d. 1538

1 Brigittine: Richard Reynolds d. 1535

2 Franciscans:

John Jones d. 1598 (Friar Observant – also known as John Buckley, John Griffith, or Godfrey Maurice)

John Wall d. 1679 (Franciscan – known at Douai and Rome as John Marsh, and by other aliases while on the mission in England)

3 Benedictines:

John Roberts d. 1610, Ambrose Barlow d. 1641, Alban Roe d. 1642

10 Jesuits:

Alexander Briant 1556-81, Edmund Campion 1540-81, Robert Southwell 1561-95

Henry Walpole 1558-95, Nicholas Owen 1540-1606, Thomas Garnet 1575-1608

Edmund Arrowsmith 1585–1628, Henry Morse 1595-1644, Philip Evans 1645-79

David Lewis 1616-79

13 Priests of the Secular Clergy:

Cuthbert Mayne 1543–77, Ralph Sherwin 1558-81, Luke Kirby 1549-82

John Paine d. 1582, John Almond d. 1585, Polydore Plasden d. 1591

Eustace White 1560-91, Edmund G(J)ennings 1567-91, John Boste 1544-94

John Southworth 1592-1654, John Kemble 1599-1679, John Lloyd d. 1679

John Plessington d. 1679

7 members of the laity – 4 men and 3 women/mothers

Richard Gwyn 1537-84, Swithun Wells 1536-91, Philip Howard 1557-95

John Rigby 1570-1600, Margaret Clitherow 1586, Margaret Ward 1588

Anne Line 1601

THE FORTY MARTYRS IN DETAIL

3 Carthusians:

The Carthusians were all priors of different Charterhouses (houses of the Carthusian Order). Summoned in 1535 by Secretary of State Thomas Cromwell to sign the Oath of Supremacy, they declined and by virtue of their Carthusian vow of silence refused to speak in their own defence.

Augustine Webster was educated at Cambridge and was prior of the Carthusian house of Our Lady of Melwood at Epworth, on the Isle of Axholme, North Lincolnshire in 1531.

John Houghton was born c. 1486 and educated at Cambridge. He joined the London Charterhouse in 1515. In 1531, he became abbot of the Charterhouse of Beauvale in Nottinghamshire but was then elected Prior of the London house, to which he returned.

Robert Lawrence served as prior of the Charterhouse at Beauvale, Nottinghamshire.

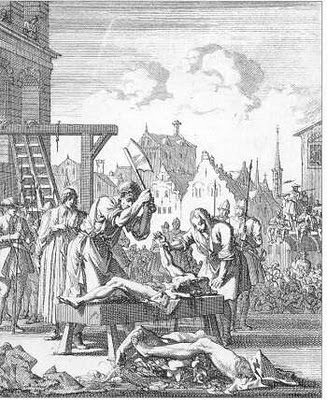

They were cruelly tortured and executed at Tyburn, making them among the first martyrs from the order in England. Beatified in 1886.

1 Augustinian friar

John Stone d. 1538

John Stone was a doctor of theology living in the Augustinian friary at Canterbury. He publicly denounced the behaviour of King Henry VIII from the pulpit of the Austin Friars and publicly stated his approval of the status of monarch’s first marriage – clearly opposing the monarch’s wish to gain a divorce. In 1538, in consequence of the Act of Supremacy, Bishop Richard Ingworth (a former Dominican, and by then Bishop of Dover) visited the Canterbury friary as part of the process of the dissolution of monasteries in England. Ingworth commanded all of the friars to sign a deed of surrender by which the King should gain possession of the friary and its surrounding property. Most did, but John Stone refused and even further denounced bishop Ingworth for his compliance with the King’s desires. He was executed at the Dane John (Dungeon Hill), Canterbury, for his opposition to the King’s wishes.

1 Brigittine

The Brigittines were an order of monks founded by St Bridget of Sweden.

Richard Reynolds 1492-1535

Richard was born in Devon in 1492 and educated at Cambridge. In 1513, he entered the Brigettines at Syon Abbey, Isleworth. When Henry VIII demanded royal oaths, Richard was along with the Carthusian priors who were hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn Tree in London after being dragged through the streets in 1535.

Two Franciscans

John Jones

(Friar Observant – also known as John Buckley, John Griffith, or Godfrey Maurice)

John Jones was from a good Welsh and strongly Catholic family. As a youth, he entered the Observant Franciscan convent at Greenwich; at its dissolution in 1559 he went to the Continent, and took his vows at Pontoise, France. After many years, he journeyed to Rome, where he stayed at the Ara Coeli convent of the Observants (A branch of the Franciscan Order of Friars Minor that followed the Franciscan Rule literally) . There he joined the Roman province of the Reformati (a stricter observance branch of the Order of Friars Minor). In 1591, he requested to return on mission to England. His superiors, aware that such a mission usually ended in death, consented and John also received a special blessing and commendation from Pope Clement VIII.

Reaching London at the end of 1592, he stayed temporarily at the house which Father John Gerard SJ had provided for missionary priests; he then laboured in different parts of the country. His brother Franciscans in England elected him their provincial. In 1596 a notorious priest catcher called Topcliffe had him arrested and imprisoned for nearly two years. During this time he met, and helped sustain in his faith, John Rigby. On 3 July 1598 Father Jones was tried on the charge of “going over the seas in the first year of Her majesty’s reign (1558) and there being made a priest by the authority from Rome and then returning to England contrary to statute” . He was convicted of high treason and sentenced to being hanged, drawn, and quartered.

The execution was to take place in the early morning at St. Thomas’ Watering, in what is now the Old Kent Road, at the site of the junction of the old Roman road to London with the main line of Watling Street. Such ancient landmarks had been immemorially used as places of execution, Tyburn itself being merely the point where Watling Street crossed the Roman road to Silchester. The executioner had forgotten his ropes! In the delay while the forgetful man went to collect his necessary ropes John Jones took the opportunity to talk to the assembled crowd. He explained the important distinction – that he was dying for his faith alone and had no political interest. His dismembered remains were exposed, but were removed by some young Catholic gentlemen, one of whom suffered a long imprisonment for this offence. One of the relics eventually reached Pontoise, where the martyr had taken his religious vows.

John Wall 1620-79

Franciscan (known at Douay and Rome as John Marsh, and other aliases while on the mission in England)

Born in Preston, Lancashire, 1620, the son of wealthy and staunch Catholics, he was sent at a young age to Douai College. He entered the Roman College in 1641 and was ordained in 1645. Sent on mission in 1648, he received the habit of St. Francis at St. Bonaventure’s Friary, Douai in 1651 and a year later was professed, taking the name of Joachim of St. Anne. He filled the offices of vicar and novice master at Douai until 1656, when he returned to the Mission, and for twenty years ministered in Worcestershire. Captured in December 1678 at Rushock Court near Bromsgrove, where the sheriff’s man came to seek a debtor. When it was discovered he was a priest, he was asked to take the Oath of Supremacy and when he refused was put in Worcester Gaol

Sent on to London, he was four times examined by Oates, Bedloe, and others in the hope of implicating him in the pretended plot; but was declared innocent of all plotting and could have saved his life if he would abjure his religion. Brought back to Worcester, he was executed at Redhill on 22 August 1679. The day previous, William Levison was enabled to confess and communicate him, and at the moment of execution the same priest gave him the last absolution. His quartered body was given to his friends, and was buried in St. Oswald’s churchyard.

3 Benedictines

Alban Roe 1582-1642

Born Bartholemew Roe 1583 in Bury, St Edmunds, Suffolk. After meeting an imprisoned Catholic recusant, he converted to Catholicism. He spent some time at the English College at Douai in northern France, but was expelled for insubordination. He spent the rest of his novitiate at the Abbey of St. Lawrence, Dieulouard, a newly opened Benedictine house near Nancy – the home of Benedictine monks fleeing persecution in England. He was ordained priest there in 1612. Sent back to England, he was banished in 1615 but returned in 1618 and was imprisoned until 1623, when his release and re-exile was organised by the Spanish Ambassador. He returned two years later for the last time and was imprisoned for seventeen years. He was hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn on the 21st of January 1642.

Ambrose Barlow 1585-1641

Born Edward Barlow at Handforth Hall, Cheshire. Until 1607 he belonged to the Anglican church, but then turned to the Catholic church. He was educated at the Benedictine monastery of St. Gregory in Douai, France, and entered the English College in Valladolid, Spain, in 1610. He later returned to Douai where his elder brother (William) Rudesind Barlow was a professed monk. Barlow also professed in 1614 and was ordained a priest in 1617. Sent to England on mission in South Lancashire, he lived with protecting families near Manchester. But he was pursued for proselytising, imprisoned five times and released, but was finally arrested on Easter Sunday 1641. Paraded at the head of his parishoners, dressed in his surplice, and was followed by some 400 men armed with clubs and swords, he could have escaped in the confusion, but he voluntarily gave himself up. Imprisoned in Lancaster Castle for four months, he was sentenced after confessing to being a Catholic priest. On Friday September 10 he was hanged, drawn and quartered at Lancaster on 10th September 1641. Many of his relics are preserved, a hand being at Stanbrook Abbey near Worcester and his skull in Wardley Hall.

John Roberts 1575-1606

John was born in 1575 the son of John and Anna Roberts of Trawsfynydd, Merionethshire, Wales. He matriculated at St. John’s College, Oxford, in February 1595 but left after two years without taking a degree and went as a law student at one of the Inns of Court. In 1598 he travelled on the continent and in Paris. Through the influence of a Catholic fellow-countryman he was converted and on the advice of John Cecil, an English priest who afterwards became a Government spy, he decided to enter the English College at Valladolid in 1598.

The following year he went to the Abbey of St Benedict, Valladolid, and from there he was sent for his novitiate to the Abbey of St. Martin at Compostella where he was professed in 1600. After completing his studies he was ordained and set out for England on the 26 December 1602. Arriving in April 1603, he was arrested and banished on 13th May. He reached Douai on 24 May and soon returned to England where he ministered among the plague-stricken people in London. In 1604, while embarking for Spain with four postulants, he was again arrested. Not being recognised as a priest, he was soon released and banished, but he returned to England at once. On 5 November, 1605, while the house of Mrs. Percy, first wife of the Thomas Percy who was involved in the Gunpowder Plot was being searched, he found Roberts there and arrested him. Though acquitted of any complicity in the plot itself, Roberts was imprisoned in the Gatehouse at Westminster for seven months and then exiled anew in July 1606.

He now founded and became the first prior of the English Benedictine house at Douai for monks who had entered various Spanish monasteries. This was the beginning of the monastery of St. Gregory at Douai and this community of St. Gregory’s still exists at Downside Abbey, near Bath, England, having settled in England in the 19th century.

In October 1607, Roberts returned to England and in December was yet again arrested and again contrived to escape after some months and lived for about a year in London, again travelling to Spain and Douai in 1608. Returning to England within a year, knowing that his death was certain if he were again captured, he was in fact captured on 2nd December 1610 just as he was concluding Mass. Taken to Newgate in his vestments, he was tried and found guilty under the Act forbidding priests to minister in England, and on 10th December was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn. His body was taken and buried in St. Gregory’s, Douai, but disappeared during the French Revolution. Two fingers are still preserved as relics at Downside and Erdington Abbeys respectively and a few minor relics exist.

10 Jesuits

Alexander Briant 1556-81

Alexander was born in Somerset about 1556 and at an early age entered Hart Hall, Oxford, where he met a Jesuit priest and became a Catholic. He then went to the English college at Reims and was ordained priest there in 1578. He returned to England and ministered in in his home county of Somersetshire. Arrested in 1581, he was taken to London and seriously tortured, though in a letter to his Jesuit companions he said he felt no pain and wondered if this were miraculous. He was barely twenty five when he was executed at Tyburn.

Edmund Campion 1540-81

Son of a Catholic bookseller named Edmund whose family converted to Anglicanism, he planned to enter his father’s trade, but was awarded a scholarship to Saint John’s College, Oxford under the patronage of Queen Elizabeth I’s court favorite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. A much sought-after speaker, he was being spoken as a possible Archbishop of Canterbury. Queen Elizabeth offered him a deaconate in the Church of England, but he declined the offer. Instead he went to Ireland to take part in the proposed establishment of the University of Dublin. Here he enjoyed the protection of of Lord Deputy Sir Henry Sidney and the friendship of Sir Patrick Barnewell at Turvey. While in Ireland he wrote a history of Ireland (first published in Holinshead’s Chronicles).

In 1571 he left Ireland secretly and went to Douai where he was reconciled to the Catholic Church and received the Eucharist that he had denied himself for the previous 12 years. He entered the English College founded by William Allen, another Oxford religious refugee. After obtaining his degree in divinity, he walked as a pilgrim to Rome and joined the Jesuits. Ordained in 1578, he spent some time working in Prague and Vienna. He returned to London as part of a Jesuit mission, crossing the Channel disguised as a jewel merchant, and worked with Jesuit brother Nicholas Owen. He led a hunted life, preaching and ministering to Catholics in Berkshire, Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire, and Lancashire. At this time also he wrote his Decem Rationes (“Ten Reasons”) against the Anglican Church, 400 copies of which found their way to the benches of St Mary’s, Oxford, at the Commencement, on June 27, 1581.

Captured by a spy, Campion was taken to London and committed to the Tower. Charged with conspiring to raise a sedition in the realm and dethrone the Queen he was found guilty. Campion replied: “If our religion do make traitors we are worthy to be condemned; but otherwise are and have been true subjects as ever the queen had. In condemning us, you condemn your own ancestors, you condemn all the ancient Bishops and Kings, you condemn all that was once the glory of England….” After spending his last days in prayer, was led with two companions to Tyburn and hanged, drawn and quartered on December 1, 1581.

Robert Southwell 1561-95

Robert was brought up in a family of Catholic aristocrats in Norfolk and educated at Douai. Moving to Paris, he was placed under a Jesuit priest, Thomas Darbyshire and after a two-year novitiate spent mostly at Tournai, in 1580 he joined the Society of Jesus. In spite of his youth he was made prefect of studies in the Venerable English College at Rome and was ordained priest in 1584.

It was in that year that an act was passed forbidding any English-born subjects of Queen Elizabeth, who had entered into priests’ orders in the Roman Catholic Church since her accession, to remain in England longer than forty days on pain of death. But Southwell, at his own request, was sent to England in 1586 as a Jesuit missionary with Henry Garnett. He went from one Catholic family to another, administering the sacraments and in 1589 became domestic chaplain to Ann Howard, whose husband, the first earl of Arundel, was in prison convicted of treason. It was to him that Southwell addressed his Epistle of Comfort. This and his other religious tracts, A Short Rule of Good Life, Triumphs over Death, Mary Magdalen’s Tears and a Humble Supplication to Queen Elizabeth, were widely circulated.

After ministering successfully for six years, Southwell was arrested. He was repeatedly tortured and badly treated so that he might give evidence about other priests. His father petitioned Queen Elizabeth that he either be brought to trial and put to death, if found guilty, or removed in any case from the filthy hole he was in. Southwell was then lodged in the Tower of London, and allowed clothes and a bible and the works of St Bernard. His imprisonment lasted for 3 years, during which period he was tortured on ten occasions. In 1595 he was charged with treason, and removed from the Tower to Newgate prison, where he was put in to a hole called Limbo.

A few days later he was indicted as a traitor under the law prohibiting the presence within the kingdom of priests ordained by Rome. Southwell admitted the facts but denied “entertaining any designs or plots against the queen or kingdom”. His only purpose, he said, had been to administer the sacraments according to the rite of the Catholic Church to such as desired them. When asked to enter a plea, he declared himself, “not guilty of any treason whatsoever”. However, he was found guilty and next day, February 20, 1595, he was drawn in a cart to Tyburn. A notorious highwayman was being executed at the same time, at a different place – perhaps to draw the crowds away – but many people came to witness the priest’s death. He was allowed to address them at some length. He confessed that he was a Jesuit priest and prayed for the salvation of the queen and his country. He commended then his soul to God with the words of the psalm in manus tuas. He hung in the noose for some time, making the sign of the cross as best he could. Some of the onlookers tugged at his legs to hasten his death, and his body was then bowelled and quartered.

As well as the religious tracts mentioned above, he left a number of poems written in prison which are considered of high literary merit.

Henry Walpole 1558-95

Henry was born at Docking, Norfolk, in 1558 and was educated at Norwich School, Peterhouse, Cambridge, and Gray’s Inn. Converted to Roman Catholicism by the death of Saint Edmund Campion, he went by way of Rouen and Paris to Reims, where he arrived in 1582. In 1583 he was admitted into the English College, Rome. On 2 February 1584, he became a probationer of the Society of Jesus and soon after went to France, where he continued his studies, chiefly at Pont-à-Mousson. He was ordained priest at Paris, 17 December 1588.

After acting as chaplain to the Spanish forces in the Netherlands, suffering imprisonment by the English at Flushing in 1589, and being moved about to Brussels, Tournai, Bruges and Spain, he was at last sent on mission to England in 1590. He was arrested shortly after landing at Flamborough for the crime of Catholic priesthood, and imprisoned at York. The following February he was sent to the Tower, where he was frequently and severely racked. He remained there until, in the spring of 1595, he was sent back to York for trial, where he was hanged, drawn and quartered on 7 April 1595.

Nicholas Owen 1550-1606

Born around 1550 into a devout Catholic family, Nicholas became a carpenter by trade, and for several years during the reign of Elizabeth I built hiding-places for priests in the homes of Catholic families. He frequently travelled from house to house under the name of “Little John”, accepting food as payment before starting off for a new project. Only slightly taller than a dwarf and suffering from a hernia, his work often involved breaking through stone, and, to minimize the chances of betrayal, he always worked alone. For some years, Owen worked in the service of Jesuit priests John Gerard and Henry Garnet. Through them he was admitted into the Society of Jesus as a lay brother.

He was first arrested in 1582 after the execution of Edmund Campion, for declaring Campion’s innocence, but later released. He was arrested again in 1594, and was tortured, but revealed nothing. He was released when a wealthy Catholic paid a fine on his behalf, the jailers believing that he was merely an insignificant friend of some priests. Early in 1606, Owen was arrested again in Worcestershire, giving himself up voluntarily in order to distract attention from priests who were hiding nearby. Under English law, he was exempt from torture, as he had been maimed a few years previously, when a horse fell on him. Nevertheless, he was racked until he died, having betrayed nothing.

Thomas Garnet 1575-1608

Thomas Garnet was born at Southwark 1575 into a prominent family. His uncle, Henry Garnet, was the Superior of all the Jesuits in England. His father Richard was at Balliol College, Oxford, at the time when greater severity began to be used against Catholics and his example and spirituality provided leadership to a generation of Oxford men who produced many other inspirational English Catholics. Thomas attended school at Horsham and at 17 was among the first students of Saint Omer’s Jesuit College in 1592. In 1595 he was on his way to study theology at Saint Albans, Valladolid, when he and five companions accompanied by Fr Tomas Baldwin were discovered in the hold of their ship by English soldiers and taken prisoner to London. After many escapades Thomas eventually reached Saint Omer again and eventually went on to Valladolid.

Ordained at 24 in 1599 he returned to England. “I wandered from place to place, to reduce souls which went astray and were in error as to the knowledge of the true Catholic Church”. During the confusion caused by the Gunpowder Plot in 1605 he was arrested near Warwick, going under the name Thomas Rokewood, which he had no doubt assumed from Ambrose Rokewood of Coldham Hall, whose chaplain he then was, and who had, unfortunately, been implicated in the plot. Imprisoned first in the Gatehouse, then in the Tower, where he was tortured in order to make him give evidence against Henry Garnet, his famous uncle, Superior of the English Jesuits, who had recently admitted him into the Society of Jesus. Henry Garnet had known of the plot and had tried to dissuade the conspirators who had confided in him. Though no connection with the conspiracy could be proved against Thomas, he was kept in the Tower of London for seven months, at the end of which he was suddenly put on board ship with forty-six other priests, and a royal proclamation, dated 10 July 1606, was read to them, threatening death if they returned. They were carried across the Channel and set ashore in Flanders.

Thomas now went to Saint Omer and then to Brussels to see the Superior of the Jesuits, Father Baldwin, his companion in the adventures of 1595. Father Baldwin sent him to the English Jesuit novitiate, Saint John’s, Louvain, where he was the first novice to be received. In September 1607 he was sent back to England, but was arrested six weeks later by an apostate priest called Rouse. This was the time of King James’ controversy with Cardinal Bellarmine about the Oath of Allegiance. Garnet was offered his life if he would take the oath, but he refused, and was executed at 32 at Tyburn, protesting that he was “the happiest man this day alive”.

Edmund Arrowsmith 1585–1628

The son of Robert Arrowsmith, a farmer, he was born at Haydock in 1585 and was baptised Brian, but always used his Confirmation name of Edmund. The family was constantly harassed for its adherence to Catholicism, and in 1605 Edmund left England and went to Douai to study for the priesthood. He was forced to quit due to ill health. He was ordained in 1611 and sent on the English mission the following year. He ministered to the Catholics of Lancashire without incident until about 1622, when he was arrested and questioned by the Protestant bishop of Chester. Edmund was released when King James I ordered all arrested priests be freed, joined the Jesuits in 1624 and in 1628 was arrested when betrayed by a young man, the son of the landlord of the Blue Anchor Inn in south Lancashire, whom he had censured for an incestuous marriage. He was convicted of being a Catholic priest, sentenced to death, and hanged, drawn and quartered at Lancaster on August 28th 1628.

Henry Morse 1595-1644

Born in Norfolk. He began studies at Cambridge and took up the study of law at Barnard’s Inn, London; at the same time he became increasingly dissatisfied with the established religion and more convinced of the truth of the Catholic faith. He went to Douai where he was received into the Catholic church in 1614. After various journeys reached Rome where he was ordained in 1623. Before leaving Rome he met the Superior General of the Jesuits with a view to joiningthe order and left for England in 1624. He was admitted to the Society of Jesus at Heaton shortly arriving in England, but almost immediately was arrested and imprisoned for three years in York Castle, where he made his novitiate under his fellow prisoner, Father John Robinson SJ, and took simple vows. Afterwards he was chaplain to the English soldiers serving in the Spanish army in the Low Countries.

Returning to England at the end of 1633 he worked in London, and in 1636 is reported to have received about ninety Protestant families into the Church. He himself contracted the plague but recovered. Arrested in 1636, he was imprisoned in Newgate and charged with being a priest and having withdrawn the king’s subjects from their faith and allegiance. He was found guilty on the first count, not guilty on the second, and sentence was deferred. While in prison he made his solemn profession to Father Edward Lusher. He was released on bail for 10,000 florins in June 1637 at the insistence of Queen Henriette Maria, wife of King Charles I. In order to free his sureties he voluntarily went into exile when the royal proclamation was issued ordering all priests to leave the country before 7 April, 1641, and again became chaplain to English regiment in the service of Spain in Flanders.

In 1643 he returned to England but was arrested after about a year and a half and imprisoned at Durham and Newcastle, and sent by sea to London. On 30th January he was again brought to the bar and condemned on his previous conviction. On the day of his execution his cart was drawn by four horses and the French ambassador attended with all his suite, as did the Count of Egmont and the Portuguese Ambassador. The martyr was allowed to hang until he was dead. At the quartering the footmen of the French Ambassador and of the Count of Egmont dipped their handkerchiefs into the martyr’s blood. In 1647 many persons possessed by evil spirits were relieved through the application of his relics.

David Lewis 1616-79

David was a Welshman of good family, born in Abergavenny, Monmouthshire, in 1616. His father Morgan Lewis belonged to an old Catholic family, but he had become a Protestant. His mother, Margaret Prichard, was Catholic, however, and all but one of their nine children were raised Catholics except David himself. After attending the Royal Grammar School at Abergavenny, David, then aged 16, was sent to London to study law at the Middle Temple. Three years later he lost interest in the legal profession and went to France as tutor of the son of one Count Savage. Probably he was reconciled to the Catholic Church while living in Paris. He then went back to Wales for a couple of years, but in 1638 he set out for Rome to study for the priesthood at the Venerable English College. Ordained a secular priest in 1642, he entered the Jesuits two years later. The Jesuit superiors sent him as a missionary to Wales in 1646 but recalled him soon afterward to be spiritual director of the English College.

In 1648 he was sent back to Wales, and there he was to remain for the next thirty years. Assigned to a remote farmhouse at the Cwm, a hideout of Jesuits and other hunted priests from miles around, David worked the Welsh-English borderlands where there were many Catholics refusing to conform to Anglicanism (recusants). For the care he gave to both their spiritual and bodily needs, they called him “Father of the Poor”. In 1678 the infamous Titus Oates claimed to have discovered an international plot to kill King Charles II and force England back into the Roman fold. Oates was a total rascal, but the very rumor of such a plot was enough to stir up a new persecution of Catholics. “Royal officials pounced on Cwm College, and the Jesuits there barely escaped. Father Lewis went into hiding elsewhere in Wales, but he was not safe for long.

The wife of a former servant set soldiers on his trail. and he was imprisoned in Monmouth for two months. Tried in March 1679 he was condemned but was then sent to London to be examined by the Privy Council on the Titus Oates Plot. Offered his freedom if he became an Anglican, he declined. He was brought back to Usk in Monmouthshire where he was hanged on August 27, 1679. The hangman fled the scene, fearing the crowd would stone him. While they were searching someone to do the job, Lewis gave such a moving speech at the gallows that it was later published. “I believe you are here met not only to see a fellow-native die, but also with expectation to hear a dying fellow native speak. I suffer not as a murderer, thief, or such like malefactor, but as a Christian, and therefore am not ashamed. My religion is the Roman Catholic one; in it I have lived above these many years; in it I now die, and so fixedly die, that if all the good things in this world were offered me to renounce my faith, all should not move me one hair’s breath from my Roman Catholic faith. A Roman Catholic I am; a Roman Catholic priest I am; a Roman Catholic priest of that religious order called the Society of Jesus I am, and I bless God who first called me. A blacksmith was found who was bribed to do the job. Lewis was so well thought of in the neighborhood that nobody gave his executioner any business ever after.

Philip Evans 1645-79

Born in Monmouth 1645 and educated at St Omer where he joined the Society of Jesus in 1665. He was ordained at Liege in 1675 and sent to South Wales where he ministered until in 1678 he was caught up in the collective that surrounded the so-called Titus Oates Plot. In that year a certain John Arnold, of Llanvihangel Court near Abergavenny, a justice of the peace and hunter of priests, offered a reward of £200 (an enormous sum then) for his arrest. Despite the manifest dangers Father Evans steadfastly refused to leave his flock. He was arrested at Sker in Glamorganshire, 4 December 1678. He refused the oath and was confined alone in an underground dungeon in Cardiff Castle.

Two or three weeks afterwards he was joined by John Lloyd, a secular priest, who had been taken at Penlline in Glamorgan (See under 13 Priests of the Secular Clergy). He was a Breconshire man, who had taken the missionary oath at Valladolid in 1649 and been sent to minister in his own country. After five months the two prisoners were brought up for trial at the shire-hall in Cardiff, charged not with complicity in the plot but as priests who had come unlawfully into the realm. It had been difficult to collect witnesses against them, and they were condemned and sentenced by Mr Justice Owen Wynne principally on the evidence of two poor women who were suborned to say that they had seen Father Evans celebrating Mass. On their return to prison they were better treated and allowed a good deal of liberty, so that when the under-sheriff came on July 21 to announce that their execution was fixed for the morrow, Father Evans was playing a game of tennis and would not return to his cell till he had finished it. Part of his few remaining hours of life he spent playing on the harp and talking to the numerous people who came to say farewell to himself and Mr Lloyd when the news got around. The execution took place on Gallows Field, Cardiff). Philip died first, after having addressed the people in Welsh and English, and saying ‘Adieu, Mr Lloyd, though for a little time, for we shall shortly meet again. John made only a very brief speech: he said, ‘I never was a good speaker in my life.’

13 Priests of the Secular Clergy

Cuthbert Mayne 1543–77

Cuthbert was born at Yorkston, near Barnstaple in Devon and baptized on St Cuthbert’s day. He grew up in the early days of the boy King Edward VI with an overtly Protestant government installed. Cuthbert’s uncle was a priest who favoured the new doctrines and it was expected that Mayne, a good-natured and pleasant young man, but with no great thought of principles of any kind, would inherit his uncle’s benefice. Educated at Barnstaple Grammar School and ordained a Protestant minister at the age of eighteen or nineteen he was installed as rector of Huntshaw, near his birthplace. There followed university studies, first at St Alban’s Hall, then at St John’s College, Oxford, where he was made chaplain. taking his BA in 1566 and MA 1570.

It was at this time that Mayne made the acquaintance of Edmund Campion and became became a Catholic. Late in 1570, a letter addressed to him from a Catholic Gregory Martin fell into the hands of the Anglican Bishop of London and officers were sent at once to arrest him and others mentioned in the letter. Mayne evaded arrest by going to Cornwall and from there went in 1573 to the English College at Douai. Ordained a Catholic priest at Douai in 1575 he left for the English mission with another priest, John Paine and took up residence with Francis Tregian, a gentleman, of Golden, in St Probus’s parish, Cornwall. Tregian’s house was raided and the searchers found a Catholic devotional article (an Agnus Dei) round Mayne’s neck and took him into custody along with his books and papers. Imprisoned in Launceston gaol, the authorities sought a death sentence but had difficulty in framing a treason indictment, but five differrent charges were brought aginst him

The trial judge directed the jury to return a verdict of guilty and he was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. Mayne responded, “Deo gratias”. Francis Tregian was also sentenced to die, but in fact he spent 26 years in prison. Two nights before his execution Mayne’s cell was reported by his fellow prisoners to have become full of a “great light”. Before his execution, some Protestant ministers came to offer him his life if he would acknowledge the supremacy of the queen as head of the church, but he declined. Mayne was executed in the market place at Launceston on November 29, 1577. He was not allowed to speak to the crowd, but only to say his prayers quietly. He was the first martyr not to be a member of a religious order. He was the first “seminary priest”, the group of priests who were trained not in England but in houses of studies on the continent.

Ralph Sherwin 1550–81

Ralph was born at Rodsley, Derbyshire, and was educated at Eton College. In 1568, he was nominated by Sir William Petre to one of the eight fellowships which he had founded at Exeter College, Oxford, probably influenced by Sherwin’s uncle, John Woodward, who from 1556 to 1566 had been rector of Ingatestone, Essex, where Petre lived. A talented classical scholar, Sherwin graduated with MA in July 1574. The following year he converted to Roman Catholicism and fled abroad to the English College at Douai, where he was ordained a priest by the Bishop of Cambrai 1577 and left for Rome and stayed at the English College, Rome for nearly three years.

On 18 April 1580, Sherwin and thirteen companions left Rome for England. On 9 November 1580, he was arrested while preaching in the house of Nicholas Roscarrock in London and imprisoned in the Marshalsea, where he converted many fellow prisoners, and on 4 December was transferred to the Tower of London, where he was tortured on the rack and then laid out in the snow. He is said to have been personally offered a bishopric by Elizabeth I if he apostasised, but refused. After spending a year in prison he was finally brought to trial with Edmund Campion on a trumped up charge of treasonable conspiracy. He was convicted in Westminster Hall on 20 November 1581. Eleven days later he was drawn to Tyburn on a hurdle along with Alexander Briant, where he was hanged, drawn and quartered. His last words were “Jesu, Jesu, Jesu, esto mihi Jesus!”

Luke Kirby (1549-82)

Kirby received his MA probably at Cambridge, before being reconciled at Louvain and entering Douai College in 1576. He was ordained a priest at Cambrai in September 1577 and left Rheims for England on May 3, 1578; however, he returned on July 15th and went to Rome. There he took the college oath at the English College, Rome in 1579. In June 1580, he was arrested on landing at Dover, and committed to the Gatehouse, Westminster. On December 4th, he was transferred to the Tower, where he was subjected to the “Scavenger’s Daughter” for more than an hour on December 9th. Kirby was condemned on November 17, 1581, and from April 2nd until the day he died, he was put in irons.

John Paine d. 1582

Paine was born at Peterborough, England, and was possibly a convert. In 1574, he departed England for Douai, where he was ordained in 1576. Immediately afterwards he was sent back to England with Cuthbert Mayne. Arrested within a year and then released he departed the island but came back in 1579. While staying in Warwickshire he was arrested once more after being denounced by John Eliot, a known murderer who made a career out of denouncing Catholics and priests for bounty. Imprisoned and tortured in the Tower of London for nine months, he was finally condemned to death and hanged, drawn, and quartered at Chelmsford.

Eustace White 1560-91

Born at Louth in Lincolnshire, his parents were Protestants, and his conversion resulted in a curse from his father. Educated at Reims (1584) and at Rome (1586), where he was ordained, he came on the mission in November, 1588, working in the west of England. Betrayed at Blandford, Dorset, by a lawyer with whom he had conversed about religion. For two days he held public discussion with a minister and greatly impressed the Protestants present. He was then sent to London, where for forty-six days he was kept lying on straw with his hands closely manacled. On 25 October the Privy Council gave orders for his examination under torture, and on seven occasions he was kept hanging by his manacled hands for hours together; he also suffered deprivation of food and clothing. On 6 December together with Edmund Gennings and Polydore Plasden, priests, and Swithin Wells and other laymen, he was tried before the King’s Bench, and condemned for coming into England contrary to law. With him suffered Polydore Plasden and three laymen.

Edmund G(J)ennings 1567-91

Edmund was a thoughtful, serious boy from Lichfield, Staffordshire, naturally inclined to matters of faith. At around sixteen years of age he converted to Catholicism. He went immediately to the English College at Rheims where he was ordained a priest in 1590, being then only twenty-three years of age. He immediately returned to the dangers of England under the assumed name of Ironmonger. His missionary career was brief. He was seized by the notorious priest catcher Richard Topcliffe and his officers whilst in the act of saying Mass in the house of Swithun Wells at Gray’s Inn in London on 7 November 1591 and was hanged, drawn and quartered outside the same house on 10 December.

Polydore Plasden 1563-91 alias Oliver Palmer

He was born in 1563, the son of a London horner. Educated at Reims and at Rome, where he was ordained priest on 7 December, 1586. He remained at Rome for more than a year and then was at Reims from 8 April till 2 September, 1588, when he was sent on the mission. While at Rome he had signed a petition for the retention of the Jesuits as superiors of the English College, but in England he was considered to have suffered injury through their agency. Captured on 8th November 1591 in London, at Swithin Wells’s house in Gray’s Inn Fields, where Edmund G(J)ennings was celebrating Mass. At his execution he acknowledged Elizabeth as his lawful queen, whom he would defend to the best of his power against all her enemies, and he prayed for her and the whole realm, but said that he would rather forfeit a thousand lives than deny or fight against his religion. By the orders of Sir Walter Raleigh, he was allowed to hang till he was dead, and the sentence was carried out upon his body.

John Boste 1544-94

John Boste was born in Westmoreland around 1544. He studied at Queen’s College, Oxford where he became a Fellow. He converted to Catholicism in 1576. He left England and was ordained a priest at Reims in 1581, before returning as an active missionary priest to Northern England. He was betrayed to the authorities near Durham in 1593. Following his arrest he was taken to the Tower of London for interrogation. Returned to Durham he was condemned and executed at nearby Dryburn on 24 July 1594. Boste denied that he was a traitor saying “My function is to invade souls, not to meddle with temporal invasions”.

John Almond d. 1612

A native of Allerton, England, he was educated in Ireland and then at Reims and in Rome. After his ordination in 1598, he returned to England as a missionary, and was arrested in 1602. John was imprisoned in 1608 for a time and arrested again in 1612. He was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn.

John Southworth 1592-1654

John Southworth studied at the English College in Douai, northern France, and was ordained priest before he returned to England. Imprisoned and sentenced to death for professing the Catholic faith, he was later deported to France. Once more he returned to England and lived in Clerkenwell, London, during a plague epidemic. He assisted and converted the sick in Westminster and was arrested again. Finally arrested and brought to the Old Bailey, he was condemned for exercising the priesthood and executed at Tyburn Gallows (hanged, drawn and quartered). His remains are now kept at Westminster Cathedral in London.

John Plesington d. 1679

Born at Dimples Hall near Garstang, Lancashire, the son of a Royalist Catholic, John was educated at Saint Omer’s in France and the English college at Valladolid, Spain. He was ordained in Segovia in 1662. Returning to England the following year, he worked in the area of Cheshire, using the aliases Scarisbrick and William Pleasington. In 1670, Father John became the tutor of the children of a Mr. Massey at Puddington Hall near Chester. He was arrested and charged with participating in the “Popish Plot” to murder King Charles II, a fabrication of Titus Oates. Despite the evidence that Oates perjured himself during the trial, Father John was found guilty and hanged at Boughton near Chester on July 19, 1679.

John Kemble 1599-1679

Born in 1599, in Herefordshire into a prominent local Catholic family. He had four brothers priests. Kemble was ordained a priest at Douai College, on 23 February 1625. He returned to England on 4 June 1625 as a missioner in Monmouthshire and Herefordshire. Little is known of his work for the next fifty three years, but his later treatment shows the esteem and affection he was held in locally. Arrested during the Titus Oates Plot confusion at his brother’s home, Pembridge Castle, near Welsh Newton. He was warned about the impending arrest but declined to leave his flock, saying, “According to the course of nature, I have but a few years to live. It will be an advantage to suffer for my religion and, therefore, I will not abscond.” He was arrested by a Captain John Scudamore of Kentchurch. It is a comment on the tangled loyalties of the age that Scudamore’s own wife and children were parishioners of Father Kemble.

Father Kemble, now 80, was taken on the arduous journey to London to be interviewed about the plot. He was found to have had no connection with it, but was found guilty of the treasonous crime of being a priest. He was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. He was returned to Hereford for the sentence to be carried out. Before he was led out for his execution Father Kemble insisted on saying his prayers and finishing his drink. The assembled party joined the elderly priest in a smoke and a drink. To this day the sayings, “Kemble pipe”, and “Kemble cup”, meaning a parting pipe or cup, are used in Herefordshire. Addressing the assembled crowd before his death, the old priest said: “The failure of the authorities in London to connect me to the plot makes it evident that I die only for profession the Roman Catholic religion, which was the religion that first made this Kingdom Christian.”

He was allowed to die on the gallows before the butchery was carried out on his body. Thus he was spared the agonies suffered by so many of the Catholic martyrs. One of the martyr’s hands is preserved at St. Francis Xavier, Hereford. His body rests in the (Church of England) churchyard of St Mary’s, Welsh Newton, and local Roman Catholics make an annual pilgrimage to his grave. Miracles were soon attributed to the saintly priest. Scudamore’s daughter was cured of throat cancer, while Scudamore’s wife recovered her hearing whilst praying at the Kemble’s grave.

John Lloyd d. 1679

He was a Breconshire man who had taken the missionary oath at Valladolid in 1649 and was sent to minister in his own country and was arrested during the Oates’ scare at Penlline in Glamorgan. Along with Philip Evans he was brought to trial in Cardiff on Monday, 5 May 1679. Neither was charged with being associated with the ‘plot’ concocted by Oates but they were charged with being priests and coming into the principality of Wales contrary to the provisions of the law. There was no sensible evidence produced against either man; nevertheless both were found guilty. The executions took place in Gallows Field, Cardiff on 22nd July 1679. Philip Evans was the first to die. He addressed the gathering in both Welsh and English saying, “Adieu, Mr Lloyd, though for a little time, for we shall shortly meet again. ” John Lloyd spoke very briefly saying, ‘I never was a good speaker in my life’.

Laymen

John Rigby 1570-1600

John was born at Chorley, Lancashire, the fifth or sixth son of Nicholas and Mary Rigby. Working for Sir Edmund Huddleston, whose daughter Mrs. Fortescue was summoned to the Old Bailey for recusancy, because she was ill, he decided to appear himself for her; he was compelled to confess his own Catholicism and was sent to Newgate.

The next day, February 14, 1600, he signed a confession saying that since he had been reconciled by John Jones, a Franciscan, he had not attended church. He was chained and sent back to Newgate, until he was transferred to the White Lion. Twice he was given the chance to repent; twice he refused. His sentence was therefore ordered to be carried out. On his way to execution, the hurdle was stopped by a Captain Whitlock, who wished him to conform and asked him if he were married, to which the martyr replied, “I am a bachelor; and more than that I am a maid”. The captain then asked Rigby for his prayers. Rigby was executed by hanging at St. Thomas Waterings on June 21, 1600. John Jones, the priest who had reconciled Rigby, had suffered on the same spot July 12, 1598.

Philip Howard 1557-95

Eldest son of the fourth Duke of Norfolk (himself executed for treason in 1572) who led a dissolute existence and left behind an unhappy wife in Arundel Castle until he was converted by the preaching of St. Edmund Campion.

Born in Strand, London, he was the eldest son of Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk and Lady Mary FitzAlan, daughter of Henry FitzAlan, 19th Earl of Arundel. He was baptized at Whitehall Palace with the Royal Family in attendance, and was named after his godfather, King Philip II of Spain.

At the age of 14, he was married to his foster sister, Anne Dacre. After years of estrangement, they were reunited and built a very strong marriage. His father was attainted and executed in 1572, but Philip Howard succeeded to his mother’s heritage upon the death of his grandfather, becoming Earl of Arundel in 1580. Arundel, and much of his family, became Catholic at a time during the reign of Queen Elizabeth when it was very dangerous to do so. They also attempted to leave England without permission. While some might be able to do this quietly, Arundel was second cousin of the Queen. He was committed to the Tower of London on 25 April 1585. While charges of high treason were never proved, he was to spend ten years in the Tower, until his death of dysentery. He had petitioned the Queen as he lay dying to allow him to see his beloved wife and his son, who had been born after his imprisonment. The Queen responded that if he would return to Protestantism his request would be granted. He refused and died alone in the Tower. He was immediately acclaimed as a Catholic Martyr.

He was buried without ceremony beneath the floor of the church of St. Peter ad Vincula, inside the walls of the Tower. Twenty nine years later, his widow and son obtained permission from King James I of England to move the body to the chapel of Arundel Castle. His tomb remains a site of pilgrimage. He was attainted in 1589, but his son Thomas eventually was restored in blood and succeeded as Earl of Arundel, and to the lesser titles of his grandfather.

Richard Gwyn 1537–84 Also known by his anglicised name, Richard White

He was born in Montgomeryshire, Wales. At the age of 20 he matriculated at Oxford University, but did not complete a degree. He then went to Cambridge University, where he lived on the charity of St John’s College and its master, the Roman Catholic Dr. George Bulloch. However, at the beginning of the reign of Elizabeth I in 1558, Bullock was forced to resign the mastership; this forced the end of the university career of Richard Gwyn, after just two years.

He returned to Wales and became a teacher, continuing his studies on his own. He married Catherine; they had six children, three of whom survived him. His adherence to the old faith was noted by the Bishop of Chester, who brought pressure on him to conform to the Anglican faith. It is recorded in an early account of his life that after some troubles, he yielded to their desires, although greatly against his stomach… But he had no sooner come out of the church but a fearful company of crows and kites so persecuted him to his home that they put him in great fear of his life, the conceit whereof made him also sick in body as he was already in soul diseased; in which sickness he resolved himself (if God would spare him life) to become a Catholic.

Gwyn often had to change his home and his school to avoid fines and imprisonment. Finally in 1579 he was arrested by the Vicar of Wrexham, a former Catholic who had conformed to the new faith. He escaped and remained a fugitive for a year and a half, was recaptured, and spent the next four years in one prison after another until his execution.

In May 1581 Gwyn was taken to church in Wrexham, carried around the font on the shoulders of six men and laid in heavy shackles in front of the pulpit. However, he “so stirred his legs that with the noise of his irons that the preacher’s voice could not be heard.” He was placed in the stocks for this incident, and was taunted by a local priest who claimed that the keys of the church were given no less to him than to St. Peter. “There is this difference,” Gwyn replied, “namely, that whereas Peter received the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven, the keys you received were obviously those of the beer cellar.”

Gwyn was fined £280 for refusing to attend Anglican church services, and another £140 for “brawling” when they took him there. When asked what payment he could make toward these huge sums, he answered, “Six-pence.” Gwyn and two other Catholic prisoners, John Hughes and Robert Morris, were ordered into court in the spring of 1582 where, instead of being tried for an offence, they were given a sermon by a Protestant minister. However, they started to heckle (one in Welsh, one in Latin and one in English) to the extent that the exercise had to be abandoned.

Gwyn was tortured often in prison, largely with the use of manacles. However, his adherence to the Catholic faith never wavered.

Richard Gwyn, John Hughes and Robert Morris were indicted for high treason in 1583 and were brought to trial. Witnesses gave evidence that they retained their allegiance to the Catholic Church, including that Gwyn composed “certain rhymes of his own making against married priests and ministers” and “That he had heard him complain of this world; and secondly, that it would not last long, thirdly, that he hoped to see a better world [this was often construed as plotting a revolution]; and, fourthly, that he confessed the Pope’s supremacy.” The three were also accused of trying to make converts.

Gwyn and Hughes were found guilty. At the sentencing Hughes was reprieved and Gwyn condemned to death by hanging, drawing and quartering. This sentence was carried out in the Beast Market in Wrexham on 15 October 1584.

Just before Gwyn was hanged he turned to the crowd and said, “I have been a jesting fellow, and if I have offended any that way, or by my songs, I beseech them for God’s sake to forgive me.” His friend the hangman pulled on his leg irons hoping to put him out of his pain. When he appeared dead they cut him down, but he revived and remained conscious through the disembowelling, until his head was severed. His last words, in Welsh, were “Iesu, trugarha wrthyf” (Jesus, have mercy on me).

Relics of Richard Gwyn are to be found in the Cathedral Church of Our Lady of Sorrows, Wrexham.

In addition, St Richard Gwyn RC High School, Flint founded in 1954 was named after him Gwyn. There is also a school of the same name in Barry, Wales.

Swithun Wells d. 1591

Wells was born at Brambridge, Hampshire, around 1536, and was for many years schoolteacher at Monkton Farleigh in Wiltshire. During this period, he attended Protestant services, but in 1583, was reconciled to the Catholic Church. In 1585 he went to London, where he took a house in Gray’s Inn Lane.

In 1591, Saint Edmund Gennings was saying Mass at Wells’s house, when the well-known priest-hunter Richard Topcliffe burst in with his officers. The congregation, not wishing the Mass to be interrupted, held the door and beat back the officers until the Mass was finished, after which they all surrendered quietly. Wells was not present at the time, but his wife was, and was arrested along with Gennings, another priest, Saint Polydore Plasden, and three laymen, John Mason, Sidney Hodgson, and Brian Lacey. Wells was immediately arrested and imprisoned on his return. At his trial, he said that he had not been present at the Mass, but wished he had been.

He was sentenced to die by hanging, and was executed outside his own house on 10 December 1591, just after Saint Edmund Gennings. On the scaffold, he said to Topcliffe, “I pray God make you of a Saul a Paul, of a bloody persecutor one of the Catholic Church’s children. His wife, Alice, was reprieved, and died in prison in 1602.

3 Laywomen – all of them mothers

Margaret Clitherow (1556–86) “the Pearl of York”

She was born the daughter of a Sheriff of York in Middleton after Henry VIII of England split the Church of England from the Roman Catholic Church. She married John Clitherow, a butcher, in 1571 (at the age of 15) and bore him two children. She converted to Roman Catholicism at the age of 18, in 1574. She then became a friend of the persecuted Roman Catholic population in the north of England. Her son, Henry, went to Reims to train as a Catholic priest. She regularly held Masses in her home in the Shambles in York. There was a secret tunnel between her house and the house next door, so that a priest could escape if there was a raid. A house once thought to have been her home, now called the Shrine of the Saint Margaret Clitherow, is open to the public; her actual house (10, The Shambles) is further down the street.

In 1586 she was arrested and called before the York assizes for the crime of harbouring Roman Catholic priests. She refused to plead to the case so as to prevent a trial that would entail her children being asked to testify, and she was executed by being crushed to death – the standard punishment for refusal to plead. On Good Friday of 1586, she was laid out upon a sharp rock, and a door was put on top of her and loaded with immense weight. Death occurred within fifteen minutes.

Margaret Ward d. 1588

Nothing is known of her early life except that she was born in Cheshire of good family and for a time dwelt in the house of a lady of distinction named Whitall then residing in London. Hearing that the priest William Watson, was confined at Bridewell Prison, she obtained permission to visit him. She was thoroughly searched before and after early visits, but gradually the authorities became less cautious, and she managed to smuggle a rope into the prison.

Fr Watson escaped, but hurt himself in so doing, and left the rope hanging from the window. The boatman whom Ward had engaged to take him down the river then refused to carry out the bargain. Ward, in her distress, confided in another boatman, John Roche, who undertook to assist her. He provided a boat, and exchanged clothes with the priest. Fr. Watson got away, but Roche was captured in his place, and Ward, having been Fr Watson’s only visitor, was also arrested.

Margaret Ward was kept in irons for eight days, was hung up by the hands, and scourged, but absolutely refused to disclose the priest’s whereabouts. At her trial, she admitted to having helped Fr. Watson to escape, and rejoiced in “having delivered an innocent lamb from the hands of those bloody wolves.” She was offered a pardon.